Enterprise AI models are improving at unprecedented speed, costs are falling, and access is no longer limited to specialist teams. Yet inside large organizations, AI remains difficult to operationalize. Despite widespread experimentation, few companies have embedded AI deeply enough to change how work gets done.

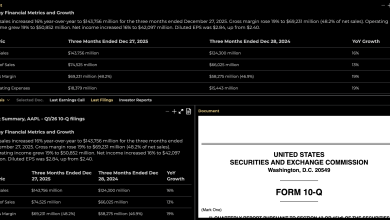

McKinsey reports that 23% of organizations are scaling an agentic AI system, and another 39% are experimenting, but in most cases, deployment is confined to one or two functions. Within any given business function, fewer than 10% of organizations are scaling AI agents at all.

What these findings point to is not a failure of the technology but a mismatch between how AI evolves and how enterprises’ digital frameworks are structured to adopt it. Previous waves of innovation, such as the rise of cloud computing, followed a similar path: early experimentation, surface-level adoptions, and a much longer lag before core processes changed. AI is following the same arc, but at a much faster pace.

The challenge then is whether enterprise operating models are designed for systems that learn, change, and improve continuously. Without this issue addressed, organizations will confuse stalled pilots with failed technology, even as underlying capabilities race ahead.

The Misalignment Problem

Many companies aren’t struggling with AI because their models or their data are weak. They struggle because their idea of how AI should work doesn’t align with the technology.

Executives tend to view AI as a strategic lever that should unlock new revenue and customer experiences. Their focus is on scale and competitive advantage. Engineering, risk, and compliance teams see AI through a different lens. To them, AI is a system of responsibility, as it must be stable and auditable. Both are right, but they optimize for different timelines and definitions of success. This divergence creates organizational drag that is frequently misinterpreted as technical failure.

This can be summed up in the ‘Mary’s Room’ philosophical thought experiment. Mary knows everything about color in theory but has never actually seen it. And when she leaves the room and experiences the reality of color, her understanding transforms instantly. Many enterprises are dealing with a similar issue: they have a fair grasp of how AI should operate in theory, but that weakens the reality of applying it to workflows.

Organizations passively learn about AI when they spend months in conceptual understanding, creating strategy decks, running ROI models, and reviewing governance documents. This isn’t the same as experiencing AI in a live workflow. Without that direct experience:

- Executives cannot manage expectations

- Engineering teams cannot assess feasibility

- Risk and compliance cannot evaluate real behaviors

- Business units cannot picture how workflows would change

This is why long planning cycles collapse under AI’s pace. Model capabilities evolve monthly, while customer expectations, regulatory requirements, and internal priorities move faster than traditional project plans can react. By the time a pilot finally emerges, maybe 6–12 months later, the assumptions behind it are already outdated.

The Breakpoints Where Enterprise AI Stalls

Even when organizations understand how AI works, they can still face a second round of friction from the structural bottlenecks embedded in enterprise delivery processes. These arise when AI is inserted into workflows that were designed for a different class of technology.

Many businesses still route AI initiatives through delivery processes inherited from traditional IT programs. These pipelines tend to include:

- Assessing feasibility

- Building a business case

- Defining requirements

- Beginning development

Yet, AI doesn’t fit this pattern. The most reliable insights about what the model can handle and where its struggles appear only once experimentation begins. Organizations are delaying hands-on prototyping while they finalize requirements, jeopardizing projects because of lost momentum long before testing begins.

Another breakdown occurs when enterprises treat AI readiness as contingent on achieving ‘perfect’ data conditions. Many organizations believe they can only adopt AI once every dataset is fully cleaned and lineage and ownership gaps are eliminated. However, these describe an ideal (and unachievable) state of enterprise data. What starts as a sensible concern quickly turns into a structural blocker.

Yet the truth is, early stages of AI deployment typically require only a narrow, well-understood subset of data from a single workflow. If businesses begin with a portion of data that is already workable and build around that, they can expand once the value is proven.

The clean-data mirage isn’t about caution but rather a pattern of delay that forms when AI is forced to wait for enterprise-wide fixes it doesn’t need to get started.

These breakpoints are symptoms of one structural reality: enterprises are trying to make AI conform to existing decision structures instead of adjusting those structures to how AI learns and improves. Organizations that make that shift unlock repeatable scaling, rather than one-off pilots.

A New Operating Model

If AI stalls because it’s routed through delivery models built for slower, more predictable systems, then the solution needs to be a different way of operating.

Push ownership to the workflow

Large steering committees struggle with AI because they’re designed to govern platforms, not evolving systems. Decision-making becomes abstract, accountability becomes muddled, and pilots linger without a clear path to production.

The more effective pattern is with smaller, cross-functional ‘AI pods’ that own specific workflows end-to-end. These pods typically would include:

- A domain or process owner closest to the workflow

- An engineer or orchestration lead

- A data specialist

- A risk or compliance partner

- And where needed, an external AI partner

Instead of owning AI as a program, these teams own outcomes: a single workflow, a defined use case, and a measurable result. This shift replaces consensus governance with responsibility. Therefore, cycles shorten, accountability becomes clearer, and fewer initiatives stall.

Replace projects to experiential cycles

Enterprises often manage AI like a finite project, starting with a defined scope, building one, deploying, and moving on. However, AI behaves more like a living system. The organizations that see progress adopt an iterative maturity loop rather than a linear plan that has a strict start and finish point.

The first stage is exposure. Teams move quickly from idea to working demo using real artifacts like regulatory documents, audits, RFPs, and client emails. The goal is not perfection but visibility and learning. By breaking the ‘Mary’s Room’ barrier, stakeholders can see and test the system in days, and with current tooling, a working demo can be built in a few weeks.

The second stage is embedding. AI is introduced to the workflow with a human-in-the-loop layer. AI flags what it can’t do; experts handle edge cases and exceptions, and corrections feed back into prompts, rules, or data. The model doesn’t improve on its own, but because humans remain actively involved. This is how quality and trust build without delaying deployment.

Only then does expansion make sense. Once one or two workflows are stable and have proven value, which should take no longer than around eight weeks, organizations can scale outward into adjacent processes or business units. AI maturity is measured by the number of reliable workflows, not the number of pilots launched.

Speed as a competitive issue

Consumers and small businesses are already reshaping how businesses operate. Just as mobile devices altered commerce over the last decade, forcing companies to prioritize mobile experiences. Now in 2025, mobile commerce is projected to account for 59% of total retail eCommerce sales. Similarly, as users grow accustomed to AI-enabled tools, from personalized recommendations to intelligent search assistants, organizations that cannot match that experience risk ceding ground to competitors who can.

AI-native firms start with a structural advantage. They carry less legacy debt, operate with fewer layers and build experimentation into daily work. As models become cheaper and more capable, these firms will absorb the gains faster, widening the experience gap. Enterprises that remain stuck aligning stakeholder risk are falling behind, not because they lack access to AI, but because their operating models can’t keep up with how quickly it improves.

Enterprise AI isn’t constrained by access or experimentation. What’s holding it back is how large organizations are trying to force AI models through infrastructure and decision cycles designed for earlier technologies. But progress comes when companies stop waiting for perfect conditions and universal agreement and instead give teams closer to the workflow real ownership, shortening feedback loops so AI can be tested, adjusted, and embedded in practice.