In June 2025, BMW announced that its Virtual Factory platform, built on NVIDIA Omniverse, had reduced layout planning time from weeks to days. The company expects production planning costs to fall by up to 30% across its global manufacturing network. Engineers now validate factory configurations virtually before physical implementation, catching conflicts and optimising material flow before concrete is poured.

This is not incremental improvement. This is a fundamentally different way of making decisions: rehearsing in simulation before committing in reality. This is the simulation-firstparadigm, and it is quietly becoming the most consequential infrastructure shift in physical industries since the move to cloud computing.

The End of the Dashboard Era

“Digital twin” has suffered from hype inflation. For most organisations, it still means a glorified 3D model with live telemetry attached, impressive in boardroom demos but irrelevant to actual operations. The industry is saturated with visualisation tools masquerading as decision infrastructure. But something substantive is changing.

The digital twin market is projected to grow from $21 billion in 2025 to $150 billion by 2030, driven by physics-informed machine learning, GPU-accelerated simulation, and standardised 3D interchange formats. This is not dashboard growth. This is infrastructure investment.

A key enabler is OpenUSD (Universal Scene Description), the 3D interchange standard originally developed by Pixar and now governed by the Alliance for OpenUSD under Linux Foundation oversight. The consortium includes Apple, Adobe, Autodesk, and NVIDIA. OpenUSD enables different tools to contribute to the same 3D scene, making multi-vendor digital twin workflows practical for the first time.

Consider the evolution. A mirror shows what an asset looks like, useful for design reviews but not much else. A dashboard shows what is happening: sensor feeds, alerts, historical trends. But a sandbox lets you ask “what if we changed it?” and trust the answer enough to act. That is the real shift: from twins as reports to twins as rehearsal spaces for the future.

The enabling technology is the maturation of AI surrogates: neural networks trained to approximate physics simulations at a fraction of the computational cost. Physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) embed physical laws directly into training, achieving speedups of 40x to 500x over traditional solvers while maintaining high accuracy. What traditionally required hours of CFD or finite element analysis can now run in milliseconds.

The Simulation-First Loop

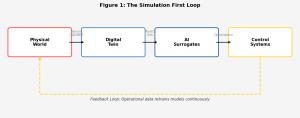

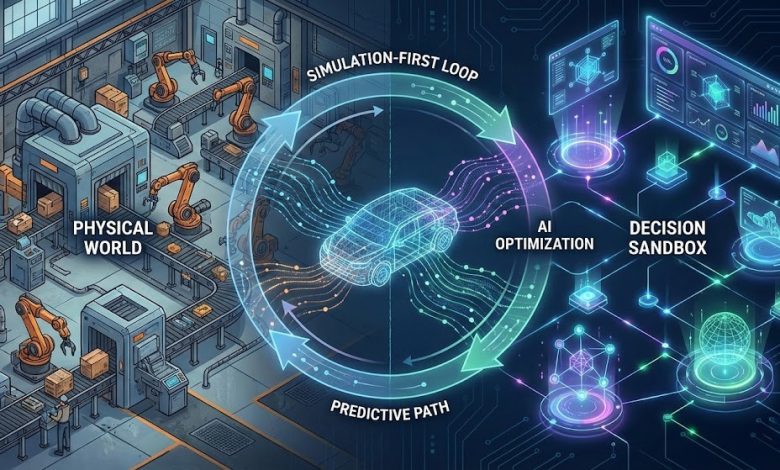

Across vendors and implementations, simulation-first systems follow a common architecture: a loop that connects the physical world to decision-making through simulation.

Figure 1: The Simulation-First Loop

The cycle begins with World to Twin: ingesting CAD, BIM, point clouds, sensor data, and operational logs to build a geometrically and semantically accurate replica of the physical system. This could be a factory floor, power grid, telecommunications network, or building.

Next comes Twin to Models: training AI surrogates on high-fidelity physics to approximate thermal, structural, fluid, or electromagnetic behaviours in real time. World models learn dynamics from video and sensor streams, capturing how equipment, people, and environments interact over time.

Then Models to Control: integrating those models into planning, scheduling, and optimisation systems. Initially, the twin informs human decisions. Over time, it validates AI controllers and agents before they touch the real system.

Finally, Control to World: new physical behaviours generate data that flows back into the twin. Models retrain. The loop tightens.

This architecture enables something genuinely new: operations where major decisions are rehearsed in simulation before execution, not occasionally for strategic plans, but routinely for daily scheduling and resource allocation.

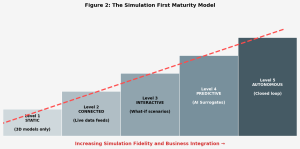

The Simulation-First Maturity Model

Not all twins are created equal. A framework for assessing maturity helps distinguish visualisation projects from genuine decision infrastructure.

Figure 2: The Simulation-First Maturity Model

At Level 1 (Static), a 3D model exists, possibly derived from CAD or BIM, but with no live data connection. This is useful for design reviews and training, but not for operational decisions.

At Level 2 (Connected), the twin receives live data from IoT sensors or SCADA systems, and dashboards visualise current state. This is where most “digital twin” deployments stall.

At Level 3 (Interactive), users can run what-if scenarios. “What happens if we increase throughput by 15%?” The twin simulates consequences, but humans interpret and decide.

At Level 4 (Predictive), AI surrogates enable real-time inference. The twin predicts equipment failures, energy consumption, and production bottlenecks with quantified confidence. Prescriptive recommendations surface automatically.

At Level 5 (Autonomous), closed-loop control emerges. The twin not only recommends but acts within defined boundaries, adjusting set points, scheduling maintenance, reroutinglogistics. Human oversight shifts from approval to exception handling.

Most organisations claiming “digital twin” capabilities are at Level 2. The strategic question is whether to invest in reaching Level 4 or 5, and for which assets that investment yields sufficient return.

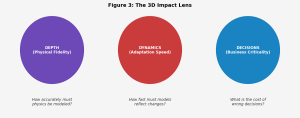

The 3D Impact Lens

A framework for evaluating where simulation-first will create the most value focuses on three dimensions.

Figure 3: The 3D Impact Lens

Depth measures physical fidelity: how accurately must the twin model underlying physics? A logistics warehouse may need only kinematic constraints, while a semiconductor fab requires molecular-level thermal and chemical simulation. Greater depth demands more sophisticated surrogates and more compute, but enables higher-confidence decisions.

Dynamics measures adaptation speed: how quickly must the twin reflect changes? A construction project updates weekly; a power grid operates in milliseconds. Faster dynamics require tighter sensor integration, more robust data pipelines, and models that retrain or adapt continuously.

Decisions measures business criticality: what is the cost of wrong decisions? A scheduling error in a warehouse causes overtime; a cooling failure in a data centre causes millions in downtime. Higher stakes justify deeper investment in simulation fidelity and validation rigour.

Assets scoring high on all three dimensions are prime candidates for simulation-first investment. This includes data centres, chemical plants, power systems, and advanced manufacturing.

The Competitive Landscape

The simulation-first stack is contested terrain. Understanding vendor positioning helps organisations make informed platform decisions.

NVIDIA has built the most comprehensive GPU-native stack through Omniverse, combining OpenUSD scene composition with physics simulation, AI training infrastructure, and robotics tooling. Their strength lies in compute density and end-to-end integration. The risk is vendor lock-in and premium pricing.

Siemens made a decisive move in March 2025, acquiring Altair Engineering for $10 billion to create the world’s most complete AI-powered design and simulation portfolio. This combines Siemens’ manufacturing execution strength with Altair’s simulation heritage, positioning them as the primary alternative for industrial customers wary of GPU vendor dependency.

Dassault Systèmes offers the 3DEXPERIENCE platform with deep roots in aerospace and automotive. Their CATIA and SIMULIA tools remain standards in regulated industries, and the platform excels at product lifecycle management. However, they have been slower to adopt AI-native architectures.

Cloud hyperscalers (AWS IoT TwinMaker, Azure Digital Twins, Google Cloud) provide infrastructure primitives rather than turnkey solutions. They offer flexibility and avoid proprietary lock-in but require significant integration effort. These are best suited for organisations with strong internal engineering capability.

Validated Industrial Impact

The business case for simulation-first is increasingly backed by documented outcomes.

BMW reports a projected 30% reduction in production planning costs, with layout planning accelerated from several weeks to just days. Engineers validate factory configurations virtually before physical implementation, catching conflicts and optimising flow before construction begins.

GE Vernova documents $1.6 billion in cumulative avoided losses across their SmartSignal predictive analytics customer base over 15 years. The platform monitors thousands of assets globally, using physics-based models to detect equipment degradation weeks before failure.

Rolls-Royce has extended maintenance intervals for some aircraft engines by up to 50% through digital twin monitoring, dramatically reducing inventory of parts and spares. The company has also saved 22 million tons of carbon through engine efficiency improvements enabled by the platform.

Refinery operators in peer-reviewed analysis of 150+ facilities report average payback periods of 1.4 to 1.7 years, maintenance cost savings of 25% to 55%, and operational efficiency improvements of 15% to 42% through digital twin deployment.

These outcomes share a pattern: the value comes not from visualisation but from the ability to predict, optimise, and prevent. The twin becomes infrastructure for better decisions rather than a reporting tool.

Toward Twin-Native Management

The deepest implication of simulation-first is not technological but organisational. If twins become the primary environment for operational decisions, they cease to be IT projects. They become something more fundamental: a second balance sheet.

In a twin-native organisation, executives manage not just physical assets but their digital replicas, a parallel portfolio that increasingly determines how those assets are used, upgraded, and expanded. This shift demands new management practices.

Explicit ownership means twins need stewards beyond IT who are responsible for fidelity, currency, and utilisation. The mindset shifts from “we have a twin for that plant” to “this plant’s twin has an owner, a budget, and measurable contributions to ROI.”

Decision hygiene requires that for any change exceeding a capital or risk threshold, at least one scenario run in the twin with documented results. This enforces management by simulation rather than slide decks, the physical-world equivalent of A/B testing discipline.

New metrics emerge alongside traditional measures like uptime, yield, and OEE. Track decision latency (time from question to tested scenario), simulation coverage (percentage of major changes rehearsed in twins), and model freshness (age of trusted models). These gauge how effectively the organisation leverages its twin portfolio.

Cross-functional alignment restructures teams around critical twins. Data engineers, operations managers, controls experts, finance partners, and sustainability leads coalesce around a shared twin as their core instrument, focused not on maintenance but on economic utility.

What Operators Should Do Now

For organisations considering simulation-first, several pragmatic steps emerge.

First, anchor on simulation-first, not vendor-first. The strategic decision is whether rehearsing decisions in simulation is core to your operations. If yes, you need a stack, but which stack is secondary to the commitment itself.

Second, assess maturity honestly. Use the maturity model to locate where you actually are, not where presentations claim. Most organisations overestimate by at least one level. Target Level 4 capability in one or two high-impact domains before broader rollout.

Third, pick flagship twins carefully. Focus on physics-intensive assets with clear data availability and quantifiable business cases. A single well-instrumented process with engaged stakeholders beats ten sub-scale proofs of concept.

Fourth, fund the plumbing. Data modelling, tag reconciliation, version control, validation frameworks: the unglamorous infrastructure that determines whether twins are trusted or ignored. Underinvestment here is the most common failure mode.

Fifth, retain architectural control. Use vendor capabilities selectively while maintaining data ownership and interface standards. Lock-in risk increases with integration depth. Modular architectures preserve optionality.

The Bottom Line

The simulation-first shift is real, but it is infrastructure, not magic. The companies that succeed will be those that treat their twin portfolio as seriously as their physical asset portfolio, with owners, budgets, governance, and measurable outcomes.

The question is not whether simulation-first matters. The evidence is accumulating across aerospace, automotive, energy, and manufacturing. The question is whether your organisation has the data discipline, talent base, and strategic commitment to execute.

The organisations that master this capability will rehearse their decisions before making them. The ones that do not will discover their errors the old-fashioned way: in production, with real consequences, at full cost.

Author’s Bio

Aditya Morey is a Senior DFX Engineer working on AI and HPC systems in the semiconductor industry. The frameworks presented here (the Simulation-First Maturity Model and the 3D Impact Lens) are original contributions developed through observation of digital twin deployments across manufacturing, energy, and infrastructure sectors. Views expressed are personal.