This article was co-authored by Richard Harang, director, data science and Younghoo Lee, senior data scientist at Sophos.

The abuse of commercial gift cards, whether in physical or digital format, is a tried and trusted method favoured by online scammers trying to con money out of people’s pockets. Unlike a demand for wire or bank transfers, where the bank or transfer service tracks the transaction and may have fraud protection in place, the only information needed to redeem the value of a gift card is its alphanumeric code, which can be easily sent via email or read out over the telephone. Once they have the code, cybercriminals can either sell the card on at a discounted rate, or they can convert the value of the card into a different currency without any trail linking them to either the gift card or their target.

While measures to limit the damage scammers can do have been implemented by most major retailers that offer gift cards, (for example, capping the value of gift cards you can buy in a day), online scammers are still managing to successfully dupe unwary targets into buying and sharing gift card information. The pretexts scammers use to convince people to send them gift card codes can vary widely, from paying off imaginary tax debts to paying for tech support software. But often, all the scammers have to do is ask.

Typically, this ask happens via email. In the case of gift card scams, the scammer will often pose as the target’s boss or an official in their company and claim to have an urgent need for gift cards. While on a victim-by-victim basis this approach is probably less lucrative than tax scams or ransoming a target’s computer back to them, it makes up for it in speed and simplicity. Scammers can send as many emails as they like (and they’re free, let’s not forget), and they only need to get lucky once to net some poor, innocent target, whom they can then work the angles with.

Anatomy of a Business Email Compromise (BEC) gift card scam

While the exact details vary per scam, the steps often follow this general pattern:

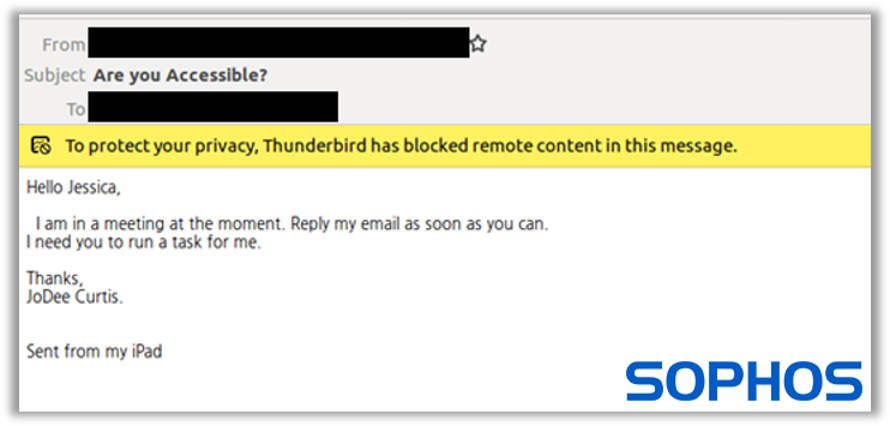

1. The contact – scammers will send out a mass email to a variety of targets, usually with a short, simple message like, “Are you there?” or “Are you available right now?”, to lure unassuming targets into responding quickly. Occasionally, they’ll step up the urgency with a subject line like, “Please respond!!!” This is because the scam relies on getting money out of targets before they’ve had a chance to think about it and realize they’re being scammed. Scammers are looking for and depending upon people who will quickly or reflexively respond to a person of authority demanding an action.

Below is an example of an initial BEC email impersonating someone and using urgent wording to set the “ask.” Note: SophosAI’s BEC model detected and blocked this email scam.

2. The ask – once scammers manage to convince a target to reply, and depending on the response time, they will then make the demand for gift cards, providing a believable reason for why they need them urgently. They’ll also likely inform the target that, for some reason, they can’t do it themselves (in a meeting, stuck in traffic, etc.). If they haven’t cranked up the urgency yet, this is where it happens: “I need this ASAP” or “This is super important, please let me know how fast you can get to this.” You don’t want to upset the boss, right?

3. The attack – once their targets have agreed to buy the gift cards, scammers send over the details, including the specific type of cards to buy, the value of each, and then instruct their target to pay out of their own pocket and then expense it back to the company, giving them reassurance that they’ll see their hard-earned cash again in their next wage packet. Scammers usually re-emphasize urgency here, by stating how important the “ask” is to the company and how fast they need the job done.

4. The loot – once targets have the gift cards in hand, scammers will then wrap-up this charade by playing on the “urgency” of the ask, telling their victim that the matter has become even more urgent, and they should just send the codes from the cards or digital vouchers over the phone or via text/email. Unfortunately, once targets do this, the scam is over, and it is likely the last time the scammers contact them.

How SophosAI models stops BEC scams

In order to effectively combat this style of scam, which relies heavily on social engineering, Sophos has taken a combination of state-of-the-art Natural Language Processing (NLP) models and hand-designed features to produce a high-performance BEC detection system. Our CATBert (Context-Aware Tiny Bert) model is based on the Transformer architecture, the same NLP architecture that powers Google’s own search tools. The key innovation behind the Transformer is the introduction of self-attention heads: sub-modules of the network which learn to understand words in context rather than individually and extract much more nuance from a block of text than simpler models, including phrases such as “urgency” and “asking for something”, which are common phrases underpinning the success of such scams.

We’ve also made further improvements to these self-attention heads with some additional features that are specific to email – including whether or not the sender and receiver share the same domain (checking if the boss in question is actually your boss), the size of the recipient list, and the number of people included in the CC field – in order to efficiently detect BEC scams, including gift card ones.

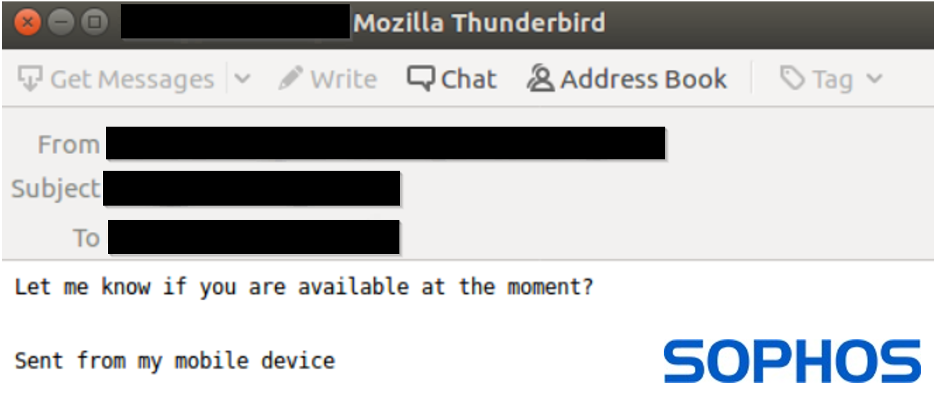

Despite the below initial “contact” email being quite short, it was still unable to slip past SophosAI’s system and was tagged as “likely malicious.” It contains all the trademark signs of a targeted BEC campaign: an external email address with a display name of a high-level company executive, a “high-urgency” subject line, and body copy requesting an immediate response.

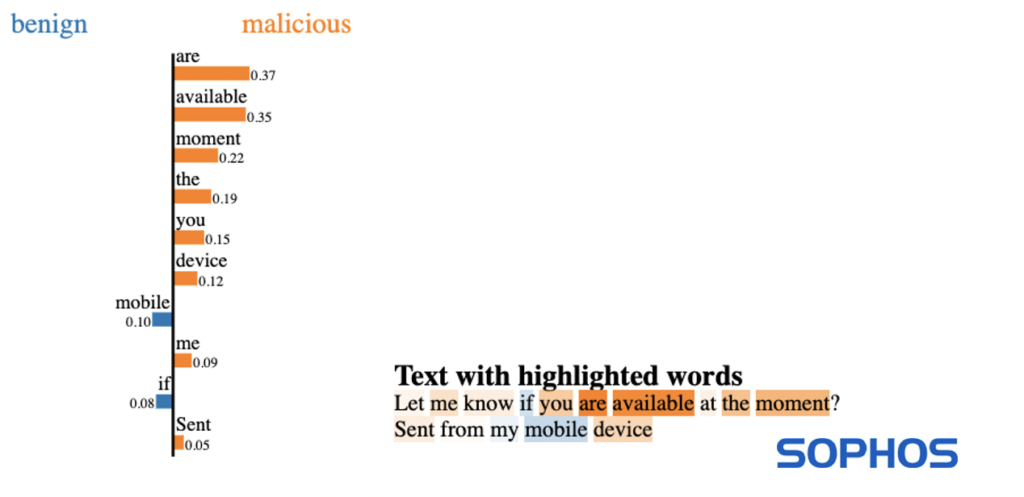

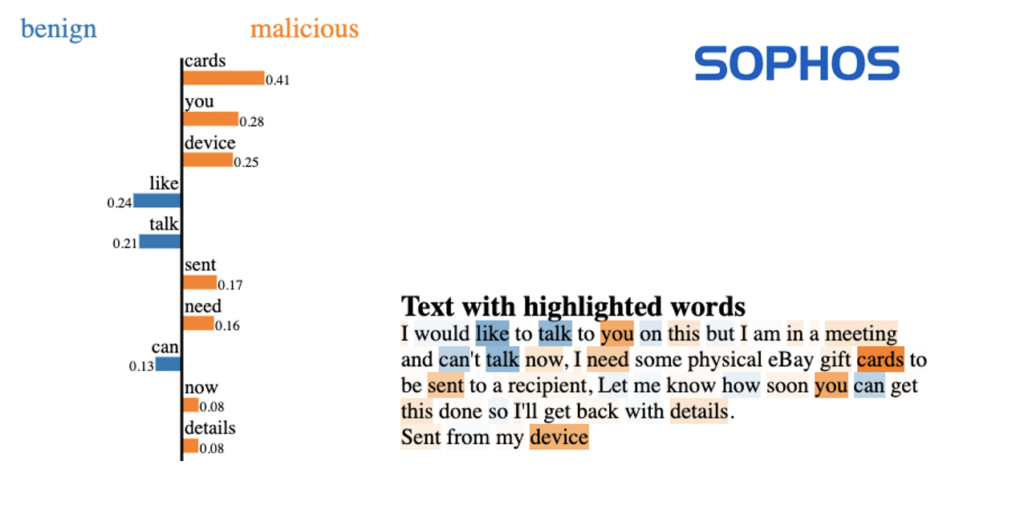

While deciphering things such as urgency directly from the model analysis is difficult, we can use a technique called LIME (https://arxiv.org/abs/1602.04938) to inspect what the model found most informative about the text of this particular email when it came to making a decision about whether or not it was a scam.

Here we can see that the model has picked out the sequence “…are available [at] the moment…” as being highly indicative of a malicious email, so it seems likely that the model has keyed in on a “sense of urgency”, combined with the email originating from an external domain as indicators of the message being of malicious intent. It’s worth noting that we didn’t have to train the model to detect “urgency” – by using the Transformer architecture combined with a number of examples of phishing emails, the CATBERT model can identify the concept of “urgency” on its own and learn to link that with phishing emails.

Unfortunately, in this particular instance, the target responded to the email, prompting an immediate follow-up from our scammers in the form of an “ask” email, which our machine learning (ML) model again scored as “likely malicious.” And again, the follow-up contained all the classic elements of the “ask” phase of a BEC attack: a request for gift cards, a convincing excuse for why they can’t talk on the phone, and an emphasis on speed and urgency. At this point, the scam was interrupted, and the attack was stopped dead in its tracks.

Once again, we can investigate the LIME outputs of the model and see that in this case, the word “cards,” particularly in conjunction with “need,” set off alarm bells for the model. What is interesting is that in a completely different context (for instance, “please sign the birthday cards in the break room”) the word “card” has almost no loading for malicious or benign either way. This is the power of self-attention – the model can evaluate the word “card” in the context of the full email and our email-specific features are able to classify it as a phishing email.

Hopefully, this example of our models in action has piqued your interest a little bit. If you want to learn more about how our ML models can detect and help interrupt this sort of attack, check out our previous post on the topic, or our talk at the DEF CON AI Village.