You can tell a market is uneasy when talk of bubbles starts to creep into otherwise optimistic updates. Analysts now question why the same small group of chipmakers, hyperscalers and model labs are committing trillions in funding and spending that largely flows between the same balance sheets. It’s not that AI itself is a fad, but that the infrastructure behind it is being financed through increasingly circular structures that make genuine demand and value creation hard to see.

Recent deals make the pattern hard to ignore. Nvidia commited up to $100 billion to OpenAI, alongside a push to anchor new AI data centres around Nvidia’s hardware. OpenAI, in turn, has entered a cloud agreement with Oracle reportedly valued at around $300 billion over its lifetime, tied to a large build-out of Oracle-run facilities in multiple US states. SoftBank has led a multibillion-dollar investment round into OpenAI while also preparing a separate programme to develop additional AI data-centre capacity. In each case, funding is closely linked to long-term commitments to consume GPUs, cloud compute or reserved capacity from the same partners.

Taken deal by deal, this looks like large firms planning for huge demand and securing the infrastructure they expect to need. Looked at together, it starts to resemble a circular loop of capital: money goes in at one end of the system as ‘strategic investment’ and comes out the other as pre-sold consumption. That makes it hard for outsiders to tell how much of the demand for AI compute is genuinely market-driven and how much has been shaped in advance by these circular agreements.

Investors are left trying to work out how much of the spend reflects genuine adoption and how much is locked in by deals designed to inflate valuations. For smaller teams and researchers, the result is higher prices and fewer options, increasing the cost of development and warding entrepreneurs and investors away from the AI industry. Chipmakers rely more on hyperscaler contracts, with more of their future pinned to a handful of buyers instead of a wider mix of customers. It looks orderly from a distance, but leaves the whole set‑up more exposed when conditions change.

When circular finance sets the terms

However, this concentration doesn’t just affect investors and suppliers; it also influences who gets to build. AI is being held up as a horizontal technology that will touch every sector, but access to high-end compute remains concentrated in a relatively small group of firms. If you’re inside the right set of partnerships, capacity is abundant and predictable. If you’re not, you live with waiting lists, volatile pricing and the risk that a big customer will always jump the queue.

Over time, that changes the kind of innovation the market sees. Teams that could build specialised models for healthcare, manufacturing, climate or local languages are forced to compromise on scale or give up altogether. Universities and public research institutions find themselves competing with large commercial labs for the same limited pool of high-end graphics processing units (GPUs), the hardware that does most of the heavy lifting in modern AI. Regional data centres that could contribute capacity struggle to participate because the biggest contracts have already been agreed elsewhere.

None of this is pre-ordained. It’s what happens when the route to market for compute mainly runs through a few very large relationships, and when financial engineering plays as much of a role as product-level competition.

A broader base for compute

There is another way to organise this. Chipmakers built their businesses by selling into a broad mix of customers: enterprises, scientific researchers, gaming, cloud platforms and specialist operators. That wider base of demand hasn’t gone away. If anything, it’s growing as more teams move from small-scale experiments to running AI in production. Chipmakers did not need circular financing arrangements to benefit from that in the past, and they do not need them now.

The real constraint is how the market is wired. Across the world, there are data centres with empty rack space and clusters that aren’t running anywhere near full tilt. On the other side are engineers, researchers and smaller companies who would gladly use that capacity but can’t sign decade-long, fixed-volume deals designed for hyperscalers. The hardware exists; what’s missing is a practical way for those two sides to meet on sensible terms.

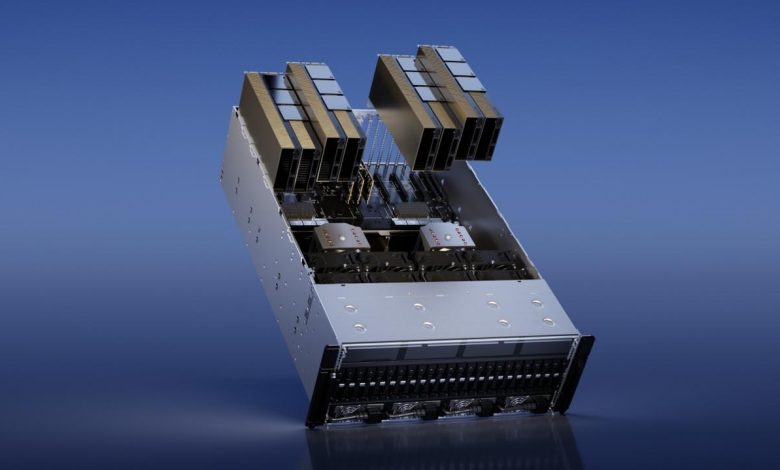

A more useful model looks like a marketplace for compute. Independent operators can bring GPUs into a common pool, publish performance, and compete on price, latency and reliability. Developers have a single way to request the compute they need, and can pull it from multiple providers instead of being tied to one cloud. Pricing follows usage and competition, not return targets set years earlier. Chipmakers don’t need guaranteed floors if they can reach a broad base of buyers through a functioning market

Decentralised networks for compute fit the bill. They organise fragmented hardware into a shared resource, reward suppliers when their machines do real work, and give builders a single interface to reach many different nodes. Networks can send jobs to where they make most sense, from high-end data-centre GPUs to specialised edge devices, and performance history can be tracked over time so that trust rests on what the network actually delivers, not on the size of a logo.

AI without the loop

As more independent suppliers connect into a market like this, total capacity rises and costs fall. That doesn’t replace hyperscalers; it sits alongside them. Large clouds will still serve organisations that want tightly integrated services, but a parallel, open market for compute gives everyone else somewhere to stand.

That diversity matters. It enables research groups outside the main hubs to run serious experiments, not just pilot models. It lets regional providers turn existing hardware into viable AI infrastructure instead of watching it idle. It gives startups a way to scale infrastructure up and down as they find product‑market fit, without long‑term commitments that could sink them if conditions change. And it gives chipmakers more options, reducing their exposure to any one buyer or business model.

Sam Altman has said that real progress in technology often comes from changing the financial model, not just the code. The question now is where that innovation happens: inside a closed loop, or in an open market that more builders can actually use.

AI will keep attracting capital; the question is how that capital is routed. Circular financing has helped a few firms move quickly, but it has also concentrated power and blurred the line between genuine demand and pre-sold consumption. If AI is going to become part of the basic fabric of business, the underlying compute market has to look more like a market and less like a loop.

AI doesn’t have to be circular. It can run on an open, contested market for compute, where hardware is supplied by many, accessed by many, and priced by use. That model is less dramatic than a trillion-dollar headline, but it is a more solid foundation for the next decade of work everyone wants AI to support.

Gaurav Sharma, CEO, io.net