Most startup founders experience 15–25% equity dilution before they reach the Series A funding round. Equity can attract investors and top talents but it comes with hidden costs that founders and employees overlook.

For employees, getting compensation in the form of equity may seem like a golden ticket to wealth, and in some cases it is. It could also be a terrible choice because if they don’t understand the rules of vesting schedules, they will walk away with nothing.

The legendary Naval Ravikant (an investor and entrepreneur) once said that to build great riches, you must own equity.

He’s right, but there’s the catch. There are hidden risks in startup equity that can drain your anticipated wealth before you ever see it. So, you must understand these hidden costs (taxes, dilutions, and vesting schedules) to secure your financial future.

In this article, we will discuss the hidden costs of startup equity and how you can turn them around in your favor.

What is Startup Equity?

Startup equity means ownership or stakes in a company at its early stages (after launch). It is also defined as the portion of ownership of a company usually issued as shares to employees, investors, and founders. Think of shares as tiny pieces of the company. If your company has a thousand shares and you own a hundred, you have 10% equity.

Initially, the founder will own 100% equity. But over time, the equity is used as currency to attract investors and talent (promise of future value) since the startup can’t afford to pay high salaries early on. If the company succeeds and gets acquired or goes public, shares can be sold for cash, making equity valuable.

Equity comes in different forms and is chosen based on the company’s growth stage, funding, and compensation strategy.

Common Stock

Common stock is the standard form of equity usually given to founders, early employees, and some investors. Common stockholders have voting rights in the company but in cases of liquidation, they only get dividends after preferred stockholders.

Preferred Stock

Preferred stock is mostly issued to investors in funding rounds. Stockholders have no voting rights but receive dividends before common stockholders and are given priority during liquidation.

For example, if a startup is sold for $10 million but investors with preferred stock agreed to get $5 million first, the common stockholders would have to split whatever is left amongst themselves.

Restricted Stock Units (RSUs)

Restricted stock units (RSUs) are not owned immediately. They are shares that a company promises to issue after certain conditions are met.

If a startup offers an employee 4,000 RSUs with a 4-year vesting schedule, and the employee leaves after one year, they only own 1,000 shares, but if they exit early, they get nothing. These shares are usually taxed as income when received.

Stock Options

In this case, employees purchase shares to gain ownership but at a fixed price (strike price). Stock options are created as incentives to reward employees for the startup’s growth and success.

If the stock price increases above the strike price, the shares are sold to make a profit. Two categories of stock options exist:

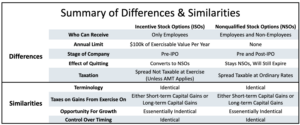

Incentive Stock Options (ISOs)

ISOs are not taxed when you exercise your stock option (you don’t have to pay income tax when you buy shares at the strike price). If you keep those shares for at least one year after exercise, they would be taxed based on the long-term capital gain rather than the ordinary income tax.

Non-Qualified Stock Options (NSOs)

NSOs can be granted to employees, contractors, advisors, and board members and do not receive preferential tax treatment. They are taxed as ordinary income on exercise.

Source: Detailed Comparison of ISOs vs NSOs — EquityFTW

Taxes on Startup Equity

Just as you owe taxes on your regular salary, equity compensation and the exercise of stock options are also subject to taxation. The IRS categorizes stock options into two main types:

Statutory Stock Options, which include Incentive Stock Options (ISOs) and Employee Stock Purchase Plans (ESPPs); and

Non-statutory Stock Options (NSOs), which are not in an ISO or ESPP plan and are taxed as ordinary income upon exercise.

Income Tax vs. Capital Tax Gains

As a stockholder, you may be liable for three different forms of taxes.

An income tax in the tax years when you purchase shares on your equity. When you sell your shares, you will be subject to capital gains tax and, for some holders, alternative minimum tax (AMT).

Income tax is applicable when:

- You receive Restricted Stock Units (RSUs) that vest gradually over time.

The fair market value of the shares at vesting is considered ordinary income and taxed accordingly.

- You exercise (or sell) non-statutory stock options (NSOs) at a price lower than the current market value of the stock. Your profit (the difference between the exercise price and the fair market value) is subject to ordinary income tax.

- You receive restricted stock without filing an 83(b) election. If you are granted 10,000 RSUs that vest when the stock price is $50 per share, the IRS considers this $500,000 in taxable income. You must pay ordinary income tax on this amount, which could push you to a higher tax bracket.

Capital gains tax only applies if you sell stock for a profit, and the tax rate depends on how long you have held the stock before selling.

There are two categories of the capital gains tax:

- Short-term capital gains tax applies when the stock is sold within one year of exercise. The tax rate can be as high as 37% for top earners (almost the same rate as ordinary income).

- Long-term capital gains tax applies when the stock is acquired more than one year before selling. The tax rate is lower (0-20%) depending on your income level.

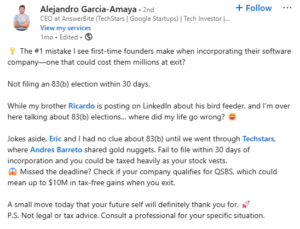

The 83(b) Election

The 83(b) election provision allows your shares to be taxed at fair market value instead of when they vest and increase in value.

If your shares appreciate later, you’ll pay taxes at the lower long-term capital gains rate instead of as regular income. Also, paying taxes upfront gives you more certainty and helps you avoid getting hit with higher taxes if the stock’s value jumps before it vests.

However, risks are attached.

If you pay taxes upfront but leave before your shares fully vest, you’ll lose that money. Worse, if the stock drops in value, you might end up paying more in taxes than your shares are actually worth.

How Dilution Shrinks Your Equity

Dilution happens when you issue new shares during fundraising rounds or employee stock option exercises. The total number of outstanding shares increases but ownership percentage and value of the shares decrease.

Let’s look at this scenario to understand better how dilution works:

A startup launched by two co-founders who initially own 100% of the company. Before raising external funding, they decided to set aside 20% of the equity for employee stock options, meaning they each now own 40% of the company, with the remaining 20% reserved for employees.

Now, the startup raises a Seed Round from investors who provide capital in exchange for 20% of the company’s equity. This is where dilution happens.

Before Investment (Pre-Money Valuation)

- Founders collectively own 80% (40% each).

- Employee stock option pool: 20%.

- Total equity: 100%.

After Investment (Post-Money Valuation)

- Founders now own 64% (32% each).

- Employee stock option pool: 16%.

- New investors receive 20% of the company in exchange for their capital.

Dilution becomes even more significant in future funding rounds (Series A, B, etc.), where additional equity is issued to investors, reducing founders’ and early employees’ ownership further.

How to Protect Against Dilution as a Founder or Employee

Dilution is an inevitable part of a company’s growth, as it helps secure funding and attract top talent. However, it’s possible to reduce its impact, such as:

Negotiating Anti-Dilution Provisions

You can negotiate terms that protect your ownership percentages during future funding rounds. For instance, “ratchet” provisions adjust the conversion price of preferred shares to ensure that early investors maintain their ownership levels, even as new shares are issued.

Understanding Pro Rata Right

These rights allow existing investors to participate in future funding rounds and maintain their ownership percentage by purchasing additional shares equal to their current holdings.

Strategic Fundraising

Fundraising is the more common cause of dilution. Carefully plan how much capital to raise and when to raise it. Raising more capital than necessary or doing so at the wrong time can lead to excessive dilution, which reduces existing shareholders’ ownership and value.

How Vesting Schedules Work

Some forms of equity cannot be owned or sold immediately but are vested (locked) until a person earns the right to own it. A vesting schedule shows the timeline and defines when the shares are fully owned by the recipient. The standard vesting schedule in startups is four years with a one-year cliff.

Here’s what it means:

- For the first year, you get nothing (no equity is vested).

- After completing one year, 25% of the equity vests all at once.

- After the “cliff” the remaining 75% vests in equal monthly installments over the next three years.

Fazlur Shah puts it best:

There are different types of vesting schedules including:

- Cliff Vesting

All allocated equity vests at a specific date in the future. For example, with a one-year cliff, 100% of the equity vests after one year of service.

- Graded (or Graduated) Vesting

Here, the equity vests in portions at regular intervals. For instance, 20% might vest each year over five years.

- Accelerated Vesting

This is when the equity vests faster than the original schedule upon certain events, such as the acquisition of the company or termination of the employee without cause.

There are two main kinds:

- Single-Trigger Acceleration: Equity vests upon a single event, like a company acquisition.

- Double-Trigger Acceleration: Equity vests when two conditions are met, typically a company acquisition followed by the employee’s termination without cause.

Examples of vesting structure: Nike and Amazon

Nike: Offers a 5% match on employee 401(k) contributions, which vest immediately. For restricted stock units (RSUs), Nike follows a graded vesting schedule, where 25% of the RSUs vest each year over four years.

Amazon: Utilizes a staggered vesting approach for RSUs. In the first year, 5% of the RSUs vest; in the second year, an additional 15% vest; in the third and fourth years, 40% of the RSUs vest each year.

If you look at most vesting structures, some common vesting mistakes founders and employees make are:

- Lack of a Vesting Schedule

Without a vesting schedule, you risk losing a chunk of equity to employees (or even co-founders) who leave too early. If they exit after just a few months but keep a large equity stake, it’ll affect the startup’s future. A vesting schedule rewards those who stay and contribute to the company.

- Exempting Founders from Vesting

In some cases, founders may leave the company for better opportunities or due to personal issues. Applying vesting to everyone including founders ensures fairness and long-term commitment.

- Misunderstanding Vesting Terms

Not fully understanding how vesting works can lead to costly mistakes. One common mistake is not realizing that leaving before the one-year cliff means forfeiting all equity. If you’re unsure about any terms, ask questions and clarify before signing anything. A simple misunderstanding could mean walking away with nothing when you expected otherwise.

Conclusion

Startup equity is like currency to founders because of the funds and talent it secures.

At launch, you own 100% of your company as a founder. But that ownership doesn’t last forever. Employees, founders, and advisors will all take a piece of that pie, and with each funding round, your stake’s value decreases due to dilution.

If you don’t plan carefully, you may own far less equity than you planned. Understanding the hidden costs of Startup equity will save your startup from costly mistakes that can affect your financial future. Understanding the hidden costs of startup equity will save your startup from costly mistakes that can affect your financial future.

Want to know how much your equity is diluted after a capital round? Find out using this FREE dilution calculator by Cake Equity.