Abstract

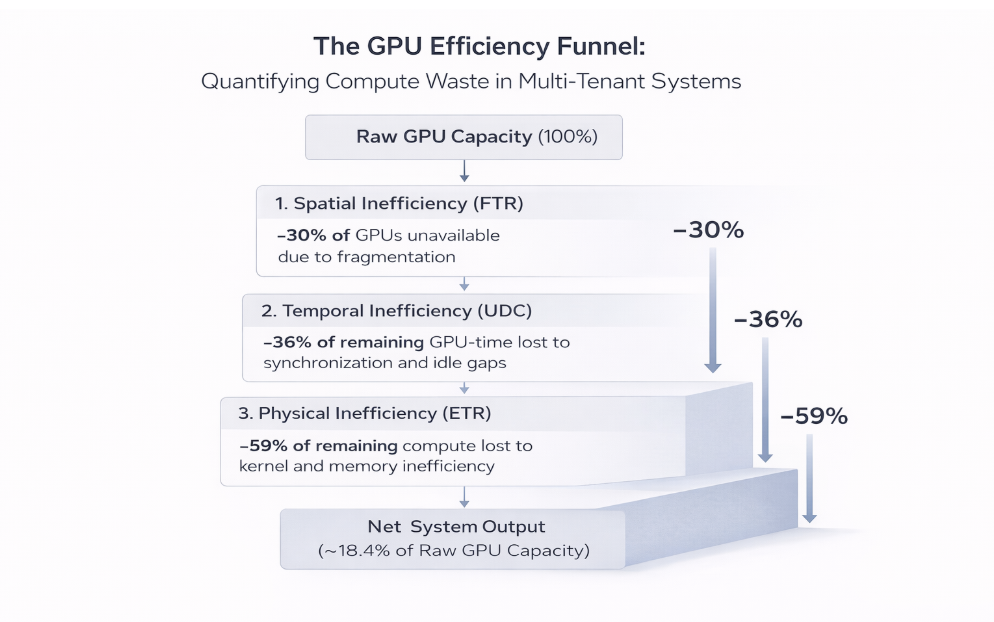

As AI clusters scale, operators face an “Efficiency Paradox”: despite purchasing state-of-the-art GPUs, real-world compute yield often falls below 20% of theoretical capacity. This paper introduces the GPU Efficiency Funnel, a framework that quantifies sequential losses across three layers: Spatial (Fragmentation Tax Rate), Temporal (Utilization Decay Curve), and Physical (Effective Throughput Ratio). Drawing on empirical data from Alibaba PAI, Microsoft Philly, and Meta’s Llama 3 training, we demonstrate how 1,000 physical GPUs can yield only 184 units of effective compute—an 81.6% efficiency loss that compounds across the three filters.

1. Introduction: The Efficiency Paradox

In modern AI infrastructure, the bottleneck is no longer just the chip; it is the cluster. Despite purchasing the fastest GPUs available, most operators observe declining real-world performance as they add more users. This is the “Efficiency Paradox.” Academic studies have documented this phenomenon: Weng et al. (2022) reported 21–42% fragmentation rates in Alibaba’s PAI platform even at 90% allocation, while Jeon et al. (2019) found average GPU utilization of just 52% in Microsoft’s Philly cluster.

To address this paradox, we must move beyond “average utilization” and examine the Yield, i.e. the final amount of productive work that survives the “Efficiency Funnel.” This paper introduces three metrics that correspond to three sequential filters, each grounded in empirical observations.

Figure 1: The GPU Efficiency Funnel. 1,000 physical GPUs yield only 184 effective compute units (18.4%) after passing through three sequential filters.

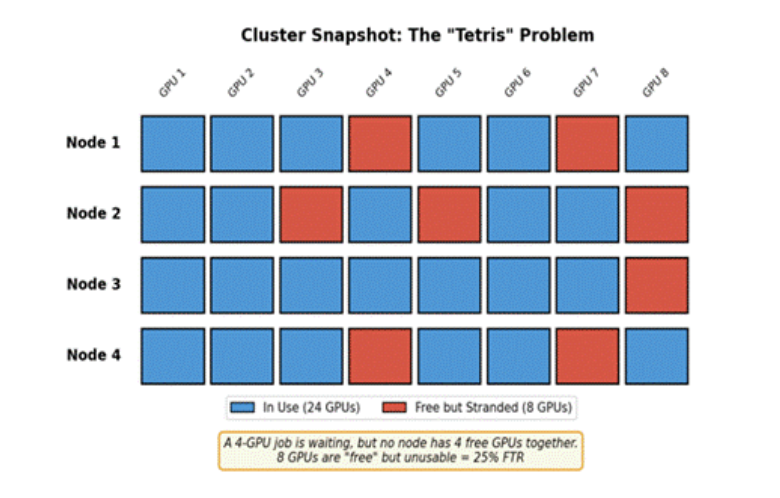

2. Layer 1: The Spatial Filter (Where)—Fragmentation Tax Rate (FTR)

The first layer of the funnel is Spatial. Before a job can run, the scheduler must find a physical location for it. This creates the problem of “stranded capacity”: GPUs that are free but cannot be used because they are in the wrong places.

2.1 Empirical Evidence

The Alibaba PAI study (USENIX ATC ’23) provides definitive evidence of the Spatial Tax. In a 6,200 GPU cluster, even when allocation hits 90%, the “Fragmentation Rate” (idle but unallocatable GPUs) ranges from 21% to 42%. These are “stranded” GPUs that cannot meet the gang-scheduling or locality needs of waiting tasks, effectively becoming paid-for, but unusable capacity.

2.2 Definition

FTR = Stranded Capacity / Total Cluster Capacity

Based on the Alibaba data, we use FTR = 30% as a representative value, meaning 30% of GPUs are effectively unavailable due to spatial fragmentation. Result: Yield = Total GPUs × 0.70

Figure 2: The Fragmentation Tax visualized. GPUs are free but stranded in unusable configurations.

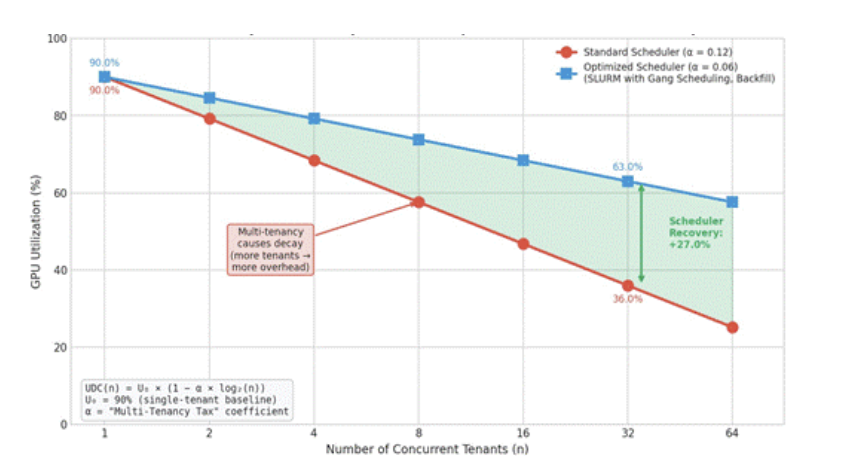

3. Layer 2: The Temporal Filter (When)—Utilization Decay Curve (UDC)

Once a job clears the spatial filter, it enters the Temporal layer. This measures time-based waste: of the GPUs that can be assigned, how much time are they actually computing versus sitting idle in wait-states?

3.1 Empirical Evidence

The Microsoft Philly study (USENIX ATC ’19) reports a median hardware utilization of 52% for allocated GPUs. Crucially, a categorical analysis of these traces reveals that 36% of the allocated window is lost to pure temporal waste: ~19% is attributable to inter-node synchronization (Wait-on-Sync/Staggered Starts) and an additional ~17% to overhead latency (Model/Data Loading). By isolating this 36% ‘Wait-Tax,’ we define a Temporal Yield of 0.64, representing the actual window available for kernel execution.

3.2 Definition

UDC(n) = U0 × (1 – α × log2(n))

Where U0 is baseline utilization (typically ~90% for single-tenant, per MLPerf benchmarks), n is the number of concurrent tenants, and α is the “Multi-Tenancy Tax” coefficient. We use log base 2 because GPU infrastructure typically scales in binary steps (2, 4, 8 GPUs per node), and each doubling of tenants adds a consistent increment of coordination overhead. Also note, the formulation above is a diagnostic model intended to capture how temporal utilization decays as a function of multi-tenancy. The UDC value of 0.64 referenced earlier is derived directly from empirical traces in the Microsoft Philly study and represents an observed point under specific workload and scheduling conditions. The UDC(n) expression is not fit to that dataset, but rather provides a generalized framework for reasoning about how scheduler-induced coordination overhead scales with tenant count across environments.

3.3 The Scheduler’s Temporal Role: The Gate Agent Problem

In a single-tenant cluster (one team, one workload), a job can start almost immediately, like a private jet. In a multi-tenant cluster with 32 different teams, the system spends significant time “switching” between jobs: clearing GPU memory, loading containers, enforcing quotas, and arbitrating priorities. This is analogous to an airport gate agent managing 32 different passenger groups; the plane spends more time on the ground than in the air.

3.4 The Scheduler’s Mitigation: Gang Scheduling

Optimized schedulers like SLURM reduce α through gang scheduling, ensuring all GPUs for a distributed job start at the exact same moment. This eliminates the “staggered start” problem where some GPUs wait idle for their partners. At 32 tenants, this can improve utilization from 36% (standard) to 63% (optimized). This improvement is illustrative of the effect of reducing the multi-tenancy tax α; actual gains depend on workload mix, scheduler implementation, and cluster design.

Note: The α coefficient is a proposed parameter for diagnostic purposes. Operators should calibrate it empirically against their own cluster telemetry. Illustrative values: α = 0.12 for standard schedulers, α = 0.06 for optimized schedulers with gang scheduling

Figure 3: Utilization Decay Curve. Multi-tenancy causes decay; scheduler sophistication determines severity.

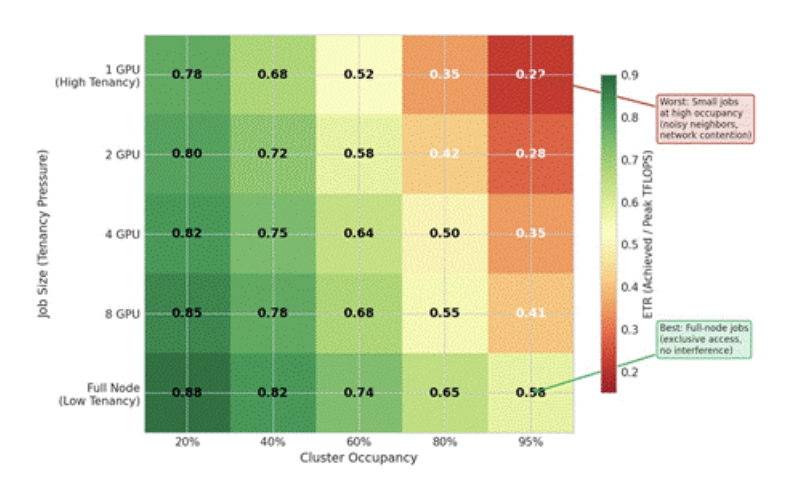

4. Layer 3: The Physical Filter (How Fast)—Effective Throughput Ratio (ETR)

The final layer is Physical. Even when a GPU is assigned and actively computing (surviving UDC), it may not be working at full speed. The Effective Throughput Ratio measures actual computational work versus the hardware’s theoretical “brochure” maximum.

4.1 Empirical Evidence

Meta’s “The Llama 3 Herd of Models” paper (2024) explicitly reports a 41% Model FLOPs Utilization (MFU) for their 405B parameter model training. This represents the “Physical Tax”—even when perfectly active, 59% of power is lost to memory-access overhead and software-to-hardware friction. Based on Meta’s data, we use ETR = 41% (a ~59% physical loss due to kernel inefficiency and memory bottlenecks). Result: Yield = Active GPU-time × 0.41, i.e. of the GPU-time that survives the Spatial and Temporal filters, only ~41% translates into effective computational work.

4.2 Definition

ETR = Achieved TFLOPS / (Allocated GPUs × Peak TFLOPS per GPU)

Figure 4: ETR by job size and cluster occupancy. Smaller jobs at high cluster occupancy suffer the largest degradation due to increased tenancy pressure. While absolute ETR varies across environments, the relative ordering and degradation patterns illustrated here are consistently observed in multi-tenant GPU clusters.

Note: Newer GPU generations and software stacks often improve absolute throughput and can raise achievable ETR for well-optimized workloads. However, the system-level losses described by the Efficiency Funnel (scheduler-induced fragmentation, temporal coordination overhead, and memory or communication bottlenecks) typically persist at scale and continue to constrain realized throughput.

5. Strategic Optimization: The Full-Node Premium

A critical finding of this framework is the Full-Node Premium. Jobs requesting an entire node (e.g., all 8 GPUs) consistently outperform fragmented jobs by 15–30% in ETR.

5.1 The Trade-off Logic

The Full-Node Premium represents a deliberate trade-off in cluster management. By enforcing full-node boundaries, an operator accepts a higher Spatial Tax (FTR) in exchange for significantly higher Physical Throughput (ETR) and Temporal Efficiency (UDC). The 15–30% gain in ETR often outweighs the fragmentation costs, making full-node allocation the “Gold Standard” for large-scale AI performance.

5.2 The Optimization Rule

Operators should prioritize the Full-Node Premium whenever the projected ETR gain (ΔETR) exceeds the projected Fragmentation Tax increase (ΔFTR). In modern LLM training, where inter-GPU communication is the primary bottleneck, “paying” the FTR tax to secure exclusive node access is almost always the mathematically superior choice.

6. Secondary Operational Constraints

While the Spatial-Temporal-Physical framework addresses the primary levers of scheduler-driven efficiency, a holistic view must acknowledge secondary “external” erosions:

- I/O Starvation: GPUs waiting for data from storage or network, starving the compute pipeline.

- Thermal Throttling: Heat-induced slowdowns when cooling capacity is insufficient.

- Resilience Costs: Re-running compute lost during hardware failures and checkpointing overhead.

These are environmental externalities outside the scheduler’s direct control. The “Big Three” (FTR, UDC, and ETR) remain the most actionable targets.

7. Industry Impact: Efficiency-as-a-Service (EaaS)

The GPU Efficiency Funnel helps explain a broader structural shift in the AI infrastructure ecosystem: value is increasingly created not by owning GPUs, but by operating them efficiently at scale.

As GPU fleets grow larger and more heterogeneous, the gap between theoretical capacity and delivered compute widens. Individual enterprises running self-managed clusters must absorb the full cost of spatial fragmentation, temporal underutilization, and sub-optimal execution efficiency. At sufficient scale, these compounded losses dominate the total cost of ownership.

In response, a class of AI infrastructure platforms has emerged that abstracts away raw hardware and instead delivers effective compute, expressed in application-level units such as tokens per second, latency, or throughput. Rather than exposing GPUs directly, these platforms internalize the operational complexity of scheduling, packing, and execution, presenting users with a simplified compute surface while managing efficiency losses internally. At sufficient aggregate demand, these platforms can amortize inefficiencies across many tenants, operating closer to the top of the Efficiency Funnel than most self-managed environments.

7.1 Operational Interpretation Through the Funnel

From a systems perspective, the business viability of these platforms can be explained using the three layers of the Efficiency Funnel:

Temporal Efficiency (UDC):

Shared inference workloads typically suffer from low utilization due to burstiness and request variability. Large-scale platforms mitigate this through batching and request coalescing strategies that smooth idle gaps and maintain higher steady-state utilization. While implementations differ, the observable outcome is flatter utilization curves under concurrent load.

Physical Efficiency (ETR):

Public benchmarks and platform disclosures show sustained throughput levels that exceed what many enterprises achieve in self-managed environments. This improvement is generally attributed to careful kernel optimization, memory-aware execution, and tight coupling between software and hardware, rather than changes to the underlying GPU architecture.

Spatial Efficiency (FTR):

At small scale, partial-GPU or fractional workloads impose significant fragmentation costs. Platforms operating at large aggregate demand can amortize this effect by pooling heterogeneous workloads, effectively internalizing the bin-packing problem while presenting users with logically “fully utilized” compute.

The intent here is to illustrate system-level patterns by which platforms operating at sufficient scale can reduce losses at each stage of the Efficiency Funnel, rather than to describe any specific implementation.

7.2 Economic Implication

The success of these platforms suggests a broader economic conclusion: the limiting factor in AI compute is no longer access to hardware, but the ability to minimize compounded efficiency loss across scheduling, utilization, and execution.

For many organizations, this reframes the infrastructure decision as a choice between:

- Owning GPUs and absorbing the full cost of fragmentation, idle time, and sub-optimal throughput, or

- Consuming effective compute from platforms that specialize in operating near the top of the Efficiency Funnel.

The GPU Efficiency Funnel provides a structured way to reason about this trade-off using observable system behavior rather than marketing claims.

8. The Integrated Framework: Calculating Total Yield

The three taxes compound sequentially. A GPU must clear each filter: spatially available (FTR), temporally assigned (UDC), then physically productive (ETR).

8.1 The Yield Formula

Effective Yield = Physical GPUs × (1 – FTR) × UDC × ETR

Physical GPUs Required = Required Workload / ((1 – FTR) × UDC × ETR)

8.2 Framework Summary (Empirical Values)

| Layer | Metric | Source | Empirical Value | Yield Remaining |

| Spatial | FTR | Alibaba PAI (ATC ’23) | 30% loss | 70.0% |

| Temporal | UDC | MS Philly (ATC ’19) | 36% loss | 44.8% |

| Physical | ETR | Meta Llama 3 (2024) | 59% loss | 18.4% |

Table 1: Empirical values for the GPU Efficiency Funnel

9. Practical Applications

9.1 Capacity Planning

A workload requiring 5,000 GPU-equivalents, with FTR = 0.30, UDC = 0.64, and ETR = 0.41, requires: 5,000 / (0.70 × 0.64 × 0.41) = 5,000 / 0.184 = 27,174 physical GPUs. Without accounting for the funnel, operators under-provision by 5×.

9.2 Scheduler ROI Justification

Improving α from 0.12 (standard) to 0.06 (optimized) in a 2,000-GPU cluster at 32 tenants increases UDC from 36% to 63%recovering 540 GPU-equivalents. At conservative cloud rates of $2/GPU-hour, this represents ~$9.5M in annualized recovered value, justifying significant investment in scheduler optimization.

10. Conclusion

The efficiency of an AI cluster is not a static hardware specification; it is a dynamic result of workload “shape” and scheduling intelligence. The GPU Efficiency Funnel, grounded in empirical data from Alibaba, Microsoft, and Meta, provides a structured methodology for diagnosing losses across Spatial (FTR), Temporal (UDC), and Physical (ETR) dimensions. The compounding nature of these losses means that 1,000 purchased GPUs deliver only 184 effective compute units. Mastering this funnel is the difference between sustainable AI economics and expensive stranded assets.

Author’s note:

The analytical frameworks and models presented in this article were developed and iteratively refined over several years through the author’s professional work in large-scale AI infrastructure forecasting, and subsequently validated and fine-tuned through real-world industry application.