When a conveyor belt breaks down at a big distribution center, it costs $100,000 every hour the system stays offline. Last quarter, equipment failures across warehouses added up to more than $50 million in lost money, based on Material Handling Industry statistics. Most of these problems happen because warehouses still watch their equipment the same way they did in 2004.

Here’s what makes it worse. Today’s warehouses run thousands of machines like conveyors, sorting equipment, storage robots, and picking systems. But most places can’t see what’s happening with all these machines at once. When something breaks, workers have to check different computer systems one by one to figure out what went wrong. By the time they find the problem, the whole warehouse has stopped moving packages.

Most warehouse monitoring works like this: each machine has its own software that doesn’t talk to the others. Your conveyor might say everything looks fine while the sorting machine next to it is having serious problems. Warehouse managers usually find out about broken equipment when workers call them from the floor, not from their computer systems. This way of doing things doesn’t work anymore as warehouses get bigger and more complicated.

That’s where Nikhil Pai comes in. He’s a systems engineer who spent years fixing exactly these problems. He builds computer platforms that change how warehouses watch and manage their equipment. Instead of ripping out old systems and starting over, he created solutions that work with what warehouses already have while letting them see everything that’s happening across all their machines.

Making warehouse machines work together

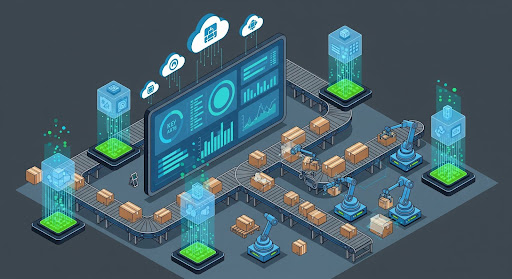

He started by changing how warehouse computers handle information. Instead of building another separate monitoring system, he created containerized Ignition platforms that grab data from many different types of equipment and process it all in one place.

His system uses MQTT and Kafka data pipelines to collect live information from conveyor controls, sorting machines, storage equipment, and robots. Each machine sends data about how fast it’s working, what errors it has, how hot it’s getting, and how much it’s vibrating. All this information goes into containers that look at the data and spot problems right away.

These containers work like portable monitoring boxes that can be set up in different warehouses without changing much of the existing setup. Each container comes ready with data collection tools, analysis programs, and screens that maintenance teams can check from any web browser.

This container setup got rid of the months it usually takes to install traditional monitoring systems. Instead of building custom connections for each warehouse, operations teams can put in identical containers that automatically figure out how to work with whatever equipment is already there.

“We needed systems that could start working in days, not months,” Nikhil Pai says. “We wanted to make advanced monitoring as easy as plugging in a printer.”

The containers talk to existing control systems, operator screens, and warehouse software without needing new hardware or shutting things down during setup. This meant warehouses could get better monitoring while keeping their normal work routines.

Real numbers show what worked

When warehouses started using his container monitoring systems, they got better at spotting equipment problems and running more efficiently. Places using these systems saw their operational efficiency go up by 15% in the first six months, based on data from multiple regional distribution centers.

This improvement came from several specific changes in how equipment was managed. The containers have built-in systems that spot potential equipment failures about 48 hours before they would have shut everything down. Maintenance crews could fix things during scheduled downtime instead of scrambling to handle emergencies during busy periods.

Being able to see equipment performance in real time lets operations managers make better routing choices based on what systems could actually handle right now, not what they handled last month. When certain conveyor sections slowed down, the system would automatically suggest different paths to keep the whole warehouse running smoothly.

For the first time, many warehouses could see their energy use patterns. This lets managers find equipment that was wasting power and fix usage during different work shifts. Supervisors got better at putting workers where they were needed because they could see where slowdowns happened most often and send extra help before problems got bad.

The Global Material Handling Equipment Market hit $188.5 billion in 2023 and should grow to $284.4 billion by 2032. Much of this growth comes from companies wanting the kind of connected monitoring that his container systems provide.

“When maintenance teams can see problems starting across all their equipment at once, they handle resources and repairs totally differently,” Nikhil Pai explains. “The old way of just reacting to broken equipment finally becomes preventing equipment from breaking.”

Growing beyond technical work

His success with container monitoring led to bigger responsibilities in product management for the regional distribution center division. This meant handling budget planning, collecting technical needs from different types of warehouses, and working with people across operations, maintenance, and company leadership.

His product management job required explaining technical stuff in business terms, making sure container development matched up with company strategy and money goals. This included managing development budgets, deciding which features different warehouses wanted most, and planning when to roll out systems across multiple distribution centers.

He also set up mentoring programs and design meetings that spread container knowledge around the company. Instead of keeping expertise in a small tech team, he built ways for more people to learn and use container solutions in different parts of the operation.

His leadership focused on training people inside the company and building tech skills that would last, rather than hiring outside consultants. This approach made sure successful container monitoring could be maintained, expanded, and changed by internal teams when operational needs shifted.

His work affected more than just individual warehouse improvements. His container success changed how the whole organization thought about adopting new technology. Other automation projects started using his deployment methods and performance tracking in their own planning.

The mixing of container technology with industrial monitoring represents a big change in how warehouses handle system integration and visibility. The Material Handling Equipment Telematics Market should grow from $7.5 billion in 2023 to $15.3 billion by 2030. This shows the industry is moving toward the connected monitoring solutions that his work demonstrates.

As supply chain demands get tougher and profit margins get tighter, being able to quickly deploy advanced monitoring across multiple warehouses will become necessary to stay competitive. The container approach that he developed gives companies a way to modernize their warehouse operations without the complicated installations that have traditionally made such projects difficult.