Much like an individual’s health, healthcare is arguably the most complex system that we have ever created. And as a consequence of our lifelong aspirations and necessity to improve, maintain or treat our own health, the systems we rely on to do so have seen a rapid evolution.

Similarly, life sciences, which was once the realm of plants, animals and humans, now extends beyond pure biology – marrying technology, pharmaceuticals and environmental research with this study of living organisms. In turn, this has led to the proliferation of new and interdisciplinary specialisations, such as biomedical devices, wearable technology and virtual reality for medical use.

As we age, adapt to new environments, are exposed to new health threats and knowledge of the human body and the conditions that affect it increase, we’re not only seeing a renaissance in how these systems practically facilitate sustained and improved health, we’ve harnessed a whole new understanding of how we respond, react and even feel in response to these interventions.

This has resulted in a gradual shift from ‘life sciences’ to ‘life services’; a refocus from cure to prevention, driven by data. The perfect storm of burgeoning knowledge, new technology and data boom has paved the way for an ever-growing demand for a personalised approach to the management of health.

So much so, that the phrase ‘personalised healthcare’ has even become something of a buzzword, discussed and deliberated on across all facets of the life science and health sectors. In many cases, this is generally regarded simply as the provision of tailored services based on an individual and their needs. However, the more we learn and understand human beings, it becomes clear that a truly personalised approach to care in fact places its primary value and emphasis on trust.

In response to this need for trust and transparency in the new digital, data-driven age, individuals want to access and control their own health and personal information at their fingertips, empowering and enabling them to play a central role in decision making about their own care and wellbeing.

This new understanding and access to sensitive and personal data come with ever greater responsibility for the healthcare and life science industries: there is a fine ethical balance to be found when protecting individual privacy whilst generating, utilising and sharing the personal data that is required to continue evolving the system, as well as supporting individuals on their pilgrimage to better health and quality of life.

What does all this mean in the long term? Essentially, we are building a system to optimise life expectancy and wellbeing. Consider the recent increase in the popularity of wearable tech devices that monitor step count. Trying to reach the often recommended 10,000 steps a day may encourage individuals to make small changes like taking walking breaks, getting outside, taking the stairs or even competing with friends. All of these actions are conscious decisions, made because of a technology device. In turn, the data generated can also be easily shared with a healthcare professional and be used to inform decision making processes relating to health care and invention. Ultimately, this all contributes to being able to make collective and individual decisions that drive healthier, happier – and longer – lives.

Many of the more recent transformations in healthcare and decision making, fundamentally come down to behaviour change. Our pre-existing emotions – including thoughts, feelings, attitudes and biases – are primal drivers in our behaviour. Which begs the question, could tracking emotion as a digital biomarker of health help determine what emotions drive certain behaviours and inform the emotional states that ultimately facilitate behavioural change? This is in fact the focus of emteq lab’s research through an InnovateUK funded project named ‘MOOD’, in which we are undertaking an in vitro longitudinal depression study, matching behavioural data such as activity type, duration and frequency with biometric data that indicates current mood state. In doing so we hope to derive further information on how behaviour changes mood, and how mood affects behaviour.

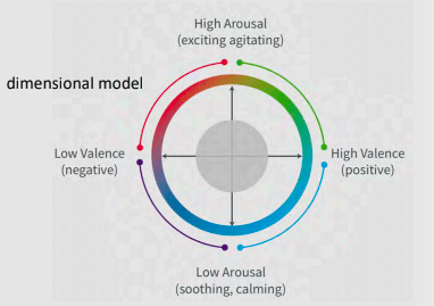

Emotions are measurable and measurement provides data. Therefore, understanding an individual’s emotional data could in fact hold the key to unlocking new habits and behaviours. Unfortunately, understanding human emotional display cannot be effectively measured via one single metric and existing emotional measurement systems, such as those relying on Ekman’s Facial Action Coding System (FACS) thus fall short. For instance, if someone smiles when they interact with another person, it could be assumed that they are expressing ‘happiness’, or at least immediate positivity. However without understanding the context in which the smile was elicited it is impractical to be impossible to know if it was meant with sarcasm or even faked – a person with depression can smile, but the smile would not be an accurate indication of emotional state. To accurately measure emotion requires the deployment of a model that correlates arousal (activation or excitement levels) with valence (positive, negative or neutral polarity levels), as outlined by Russell’s model of affect. [see Image 1].

By measuring each of these variables using technology an individual is comfortable and familiar with, we can genuinely start to paint a picture of a person’s true emotional state. Layering this on top of measures of physical health and wellbeing means that healthcare professionals can then truly understand someone on a holistic, individualised level which enables the creation of a further personalised healthcare experience. This deep, multi-level understanding of a person means that genuine trust can be built and AI can use the data to identify the appropriate support mechanisms and better inform medical advice, diagnostics and interventions.

As well and identification of the correct management protocol, AI can also play an important role in ‘dosage control’ for interventions such as exposure therapies, empowering self-guided and remote treatments where digital technology is used to track measurable outcomes, e.g. physical reactions to an individual’s mental state – heart rate, electromyography (EMG) to determine nerve and muscle function, gaze or eye tracking, and so on. Collecting these objective sources of measurement opens the opportunity for the exploration of digital phenotyping, based on the context of the individual’s lived experience, rather than a one-size-fits-all approach.

However, as AI continues to develop and is capable of collecting more individual data, the ethical challenge deepens – but again, this comes back to trust. In an age where concerns of ‘Big Brother’ are significant, issues of over-surveillance and responsible data collection need to be directly and clearly addressed. The companies performing well are those demonstrating the active steps they are taking to protect patient data and there is also something to be said for enabling individuals to feel empowered in knowing their own data, particularly in terms of health, is contributing to improving a service or contributing to a greater ‘good’.

In testament to this, the King’s College London’s Covid-19 Symptom Tracker app has had nearly 4 million downloads in the UK under its altruistic incentive to help scientists better understand the symptoms of the virus by analysing and predicting its spread in real time. Therefore, health tech companies that can find ways to incentivise patients to share their data by demonstrating a genuine value exchange built on trust and empowerment, will create thriving, transparent networks, ultimately encouraging innovation.

Undoubtedly, there needs to be greater regulation for use of AI to personalise healthcare and all that this entails in order to protect patients. The FDA is preparing to regulate medical products that use data from AI and machine learning and NHS AI Lab is also working with several regulators across the UK to establish a clear pathway for the regulation of machine learning. This is no easy feat, as the technology advances quickly and so regulatory frameworks must adapt and be clear on how much advancement is permissible before re-certification is needed. And with AI being used right around the world, is country-specific regulation enough, or should we be pursuing a joined-up global system? After all, technology knows no borders.

Regulatory frameworks will also need to address the matter of access to AI healthcare innovation to ensure that innovative, personalised medical treatments are not only available to a subset of the population who can afford it, resulting in data sets that are skewed by those that can. For example, in the US, which operates through an insurance-based system, those with mental health disorders who could really benefit from treatment using VR, could be at risk of higher premiums or reduced coverage if they have a pre-existing mental health condition and as a consequence, would be unable to access it.

Fundamentally, individuals should own their data in perpetuity and understand how their data will be used before agreeing to share it. Trends towards creating value exchanges that benefit individuals as well as the overall system will continue to grow as the capabilities of VR and AI further develop and become more integrated into our healthcare systems. There is a real possibility of a future where data becomes our currency and data owners (individuals) become their own brokers; anything is possible.

But for now, where we are currently lacking in regulation for these technologies that are evolving at lightning speed, the industry as a whole and individual companies must assume responsibility. By demonstrating that they are trustworthy stewards of personal data, innovators are more likely to succeed in building trust with individuals, which will ultimately unlock a world of opportunity for us all.