I was recently reading a blog on the London Review of Books website. Written under a pseudonym by ‘Mark Papers’, and entitled Closed Loops, the blogger is an academic, writing about how Generative AI is changing ways of working in universities for students and lecturers alike.

Discussing how their students are using ChatGPT and similar Generative AI tools to complete essays and other homework, and how lecturers too are using such technologies to mark student’s work, the blogger wonders where this could lead:

‘… it isn’t hard to imagine a perfect closed loop in which AI-generated syllabuses are assigned to students who submit AI-generated work that is given AI-generated feedback.’

A thought experiment perhaps? An extreme point of using AI in university teaching is that nobody learns anything and surely not much research and development occurs, not in the long term at least.

Generative AI – opportunities and limitations

I was prompted to think about similar extremes again when I recently read a thoughtful post on LinkedIn by Andrew Burgess. In his post, Burgess was highlighting what he could see as the inevitable end-point of using the large language models (LLMs) that drive Generative AI to create written content.

‘There are plenty of short-term risks in using LLMs, but one of the big, longer-term risks will creep up on us without us hardly noticing. As all the content that has been generated by the LLMs gets used to further train the model (the digital version of the mythical Ouroboros), we will get a slow but significant degradation in the quality of the written word. Everything will start to read like it was written by an over-enthusiastic copywriter.’

While I can see the risk Burgess discusses, I disagree with this point of view, at least from the perspective of creative writing outside of the business world. As and when this kind of quality degradation caused by AI comes to the world of literature, I hope the response will be a leap in creativity and innovation by authors and poets, showing just how resourceful and nuanced humans can be in comparison to AI-generated content.

Generative AI is an extremely useful tool, I use it most days at work, to write programming code, generate presentations, create process diagrams, and all kinds of things. I pretty much always need to amend the generated content, tweak it to either get it to work, make it look and read more fluidly, to correct it in some way. Sometimes I throw away the content created by the LLM and start over with another prompt. But such material is great for boilerplate content: a starting point I can then correct and further refine to suit my needs.

I also lead a team of AI Engineers, Architects, and Data Scientists. Together we innovate with machine learning and Generative AI, exploring how AI systems and Agents can transform business ways of working. In so many ways I am an advocate for Generative AI and AI more widely… but it does have its limitations.

The emotion of art: Human vs AI

One of the observations of Mark Papers that resonated with me when I read their LRB blog was their encounters with content in student essays that they suspect has been generated by AI.

‘Now I occasionally come across writing that is superficially slick and grammatically watertight, but has a weird, glassy absence behind it.’

It resonated because that ‘weird, glassy absence’ is what I often feel when I look at artwork generated by AI. While the images I look to may be full of colour and shape, it feels like they lack emotion. In this context the word ‘feeling’ is important. Given the AI being used to generate the image I see is derived purely from mathematics and logic, it’s no surprise to me that there is a feeling of objectivity, no empathy, or the feelings I experience when I look upon art that carries emotion.

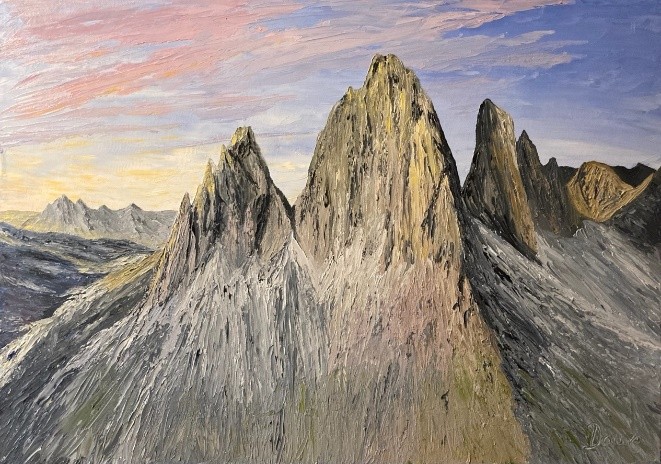

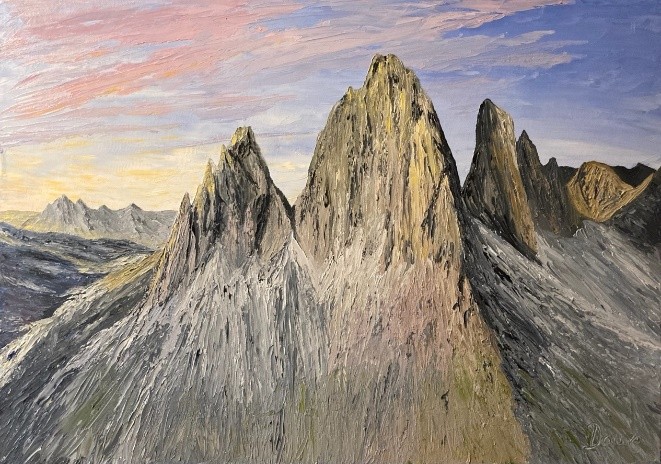

I must profess to carry my own biases here! While in my day job I am a Chief Data Scientist, I am also an artist. I paint, mostly oil paintings of mountain landscapes.

I’m a self-taught artist. My background is not artistic; I studied Maths at University, have an MSc in Statistics and was an early data scientist – I’ve been building data science teams and associated advanced analytics and AI products and services for nearly 20 years.

While data science is in many ways a creative, problem-solving profession, I think one of the reasons I started painting around a decade ago was because I yearned for something different from the probability distributions, mathematical formulae, data structures, and computing code that so often spin around my mind. I do relish the many intellectual challenges of my job, but I have also come to depend on the emotional release that painting offers me.

It’s a completely different way of thinking. When I spread oil paint across a canvas into the colour of the sky, the shapes of clouds and mountains, I am not just making images, I am imbuing them with feeling – of how the mountains and painting images of them change my mood. I also seek to capture the mood and feeling of the mountains themselves.

If all this sounds quite ‘arty’ then I write it quite deliberately. Through painting, I have learned what art does for me, and this has led me to both understand and value the process of making art.

In its broadest sense, art is a means of communication. Good and bad, happy and sad, light and dark, many more superlatives, and everything in between. Making art enables us to express ourselves and, when we look at art, it can speak to us. Such terms are cliched, but that’s because they are true.

The value of intuition

Both the examples I cite in the LRB blog and LinkedIn post above are of AI going to extremes: a closed loop of AI writing and then marking homework leading to no real learning for the student, a world where the quality of the written word is degraded by AI to the point that all writing is superficial, essentially the same. If these are examples of AI extremes, then what is the endpoint?

Around two years ago I read Novaceneby James Lovelock. Published in 2019 and his last book before his death, aged 103, in 2022, Novascene is Lovelock’s view of the future, one in which humanity has been superseded by hyperintelligent machines as the dominant species on Earth.

The stuff of science fiction? Lovelock was used to being doubted. Now considered one of the great visionaries of the 20th Century, Lovelock’s Gaia Hypothesis – that the Earth is a single, self-regulating system – was viewed skeptically when he co-developed it in the 1970s with the microbiologist Lynn Margulis. But look at the climate emergency, how the Earth’s environmental balance is now being tipped as the carbon we pump into the atmosphere is reducing the planet’s capacity to regulate and cool its weather systems, and Gaia does not seem far-fetched at all.

One of Lovelock’s key observations throughout Novascene is how humans are increasingly seeking to promote logical, objective thought processes above any other means of decision-making. Perhaps surprisingly for an engineer, Lovelock also laments how we do not value our intuition:

‘… we have been too reliant on language and logical thinking and have not paid enough attention to the intuitive thinking that plays such a large part in our understanding of the world.’

The development of today’s sophisticated Generative AI can be seen as our latest step in the advancement of the language-driven, logical means of thinking that Lovelock describes. If past events have been recorded in some way: written down, sketched, tabulated, sound or video captured, they can be used to train an LLM. The LLM, trained on a vast amount of such data, can recall any of this data and play it back to us in the ways we ask (unless of course, it hallucinates).

Can AI ever intuit?

And one thing no AI can currently do today is intuit: to determine by instinct what it should recommend or do next. There is no such thing as instinct or imagination to AI – it cannot create anything truly novel – it’s simply an extremely good recollection machine.

I’m not sure if the mathematics that could be used to build AI that can intuit has yet been discovered or whether it even exists at all. Given Lovelock’s views on logical reasoning and intuition, it’s quite likely his thinking would have been that such AI would not be driven by mathematics but something altogether different, something the large AI builders such as OpenAI and Google are probably not anywhere close to thinking about right now, as they continually compete to win the battle of the LLMs.

Observing the current super-fast pace of AI development and considering all of this, I can’t help but think about painting. The interesting thing is that, when I stand at my easel making art, I think quite differently compared to any of the logical reasoning I do as a data scientist.

I feel like I’m in an altogether different head place. In the zone, moving with the flow, letting my feelings take over to the point that it can feel like the painting appears before my eyes in a process I’m almost not conscious of. Sometimes, long after I’ve painted a scene, I look back on it and wonder about the state of mind I was in. Making art encourages me to intuit, and I think knowing this enables me to be more conscious of how to think intuitively, even if I can’t always remember doing it.

I think AI-generated art and other such text and image content will always have a sense of the ‘weird, glassy absence’ until we work out a way for AI to be intuitive and creative. Maybe this is the last great problem, for us at least. When it’s solved, Lovelock’s hyperintelligent machines could come forth and replace us as the dominant species on the planet.

Of course, we don’t need to look at this as a done deal. While Lovelock was quite content that such an epochal change would be a good thing for the Earth (he believed the incoming machines would save Gaia from the climate emergency), we still have a choice of whether we seek to solve this last great problem.

The question is whether we will recognise this as a choice. Like students and teachers first writing and then marking essays using generative AI, we humans tend to choose the easiest option. As someone who uses ChatGPT, I need to recognise that using generative AI to write words or programming code for me is the easy option and that there is a risk I do so at the expense of my learning. Such learning is important, it fosters the problem-solving skills and critical thinking that facilitates creative innovation.

More widely, awareness of how the use of AI risks human intellectual development could be used by policy-makers to develop AI regulations that protect human creativity and innovation. Ultimately, however, I think it comes down to each one of us using AI to recognise the value of our minds when seeking to solve a problem or make something new.