The following case study is based upon a multi-year programme delivered in Rolls-Royce Group and

is based on my experiences as the project sponsor and owner and de facto behavioural science lead.

Following the approval of the business case in late 2019/early 2020 to implement a new digital

platform to cover all the direct spend for Rolls-Royce worldwide a value of approximately £8 Billion

annually and over 2,000 vendors the project was abruptly intercepted by the Covid-19 global

pandemic in mid-March 2020. Signalling not only the way in which the design and delivery could be

achieved would be virtual but so too the engagement model for stakeholders, implementers, and

adopters. In essence this became the catalyst and archetypal “Trojan Horse” to take a new approach

to the way the programme approached the non-technology related aspects of the programme.

Namely, Change, communication, engagement, adoption and ownership of the end solution across

the eco system of solution provider, programme team, support partners, stakeholders, end users

and our supply chain partners (Tier 1 to Tier 4).

Setting the context for this programme is equally key in recognising the significant challenge and in

turn achievement of the assembled team that delivered a step change in adoption of a new digital

platform across a wide spectrum of geographies and teams within the business. At a headline level

recognising that the pandemic had all but halted air travel in its tracks within a matter of days,

whereby flying hours were down by nearly 90% in the first quarter of the pandemic, salient when

the business model is in its simplest from “power by the hour”! As events unfolded and the return

to 2019 levels of flying became less likely by the day the business was faced with the inevitable

decision of making the tough decision to revise engine build plans (for the Civil division, being

approximately 2/3rds of the total group turnover) and after a number of reforecasts of the build

programme when the norm is to produce 1, the resulting well publicised job losses ensued (9,000 in

total). When this is factored in with personal circumstance of enforced lockdowns, remote working,

people contracting Covid-19, etc. then the Cognitive load ₁ becomes significant. In short we only

have so much “processing capacity mentally that by adding complex and uncertain variables all at

once we can only focus on some not all of the things that are happening to us.

From a wider digital adoption perspective, the news has not been good supported by a number of

surveys and insights collected by many of the well known players for management reporting. Some

of the sobering facts that have been pulled from the reports identified below as being reasons why

adoption is a number one priority if business benefits are to be delivered. To get the most from

digital transformation, companies need to know the challenges and avoid the pitfalls such as

resistance to change, developing in advance the right skills internally, getting into the detail of

compliance and cyber security issues and concerns all of which impede programmes along with the

difficulties of measuring ROI.

- More than 50% of digital transformation efforts fizzled completely in 2018. (Forrester)

- 70% of digital transformations fail, most often due to resistance from employees. (Mckinsey)

- Only 16% of employees said their company’s digital transformations have improved

performance and are sustainable in the long term. (Mckinsey) - Companies report digital transformation is still often perceived as a cost centre (28%), and

data to prove ROI is hard to come by (29%). Cultural issues also pose notable difficulty, with

entrenched viewpoints, resistance to change (26%), and legal and compliance concerns

(26%) stymieing progress. (Prophet)

Therefore, in designing an approach to ensure that we gained maximum benefit for all parties we

had to take an approach that recognised fully “the situation, the context and the people involved (at

an individual level as reasonably possible)”. Looking at this challenge from a behavioural science

perspective (given the focus of my own PhD journey) it became apparent that a “traditional”

approach to change with training delivered in a classroom environment was clearly not going to be

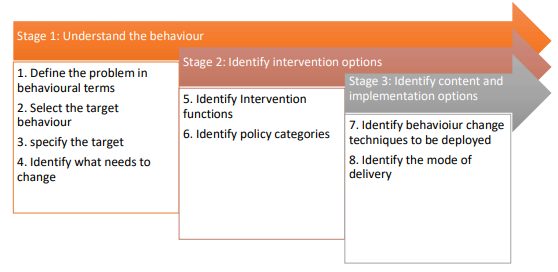

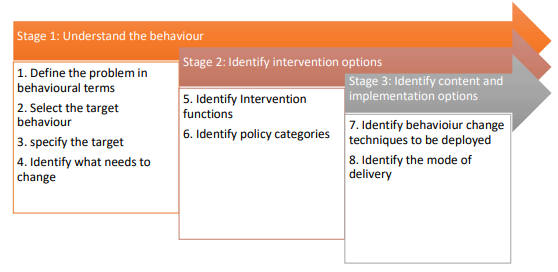

effective. Hence taking a 3 stage approach that is well known in academic circles effectively

summarises the steps we had to take in defining an effective solution that would be impactful and

deliver adoption.

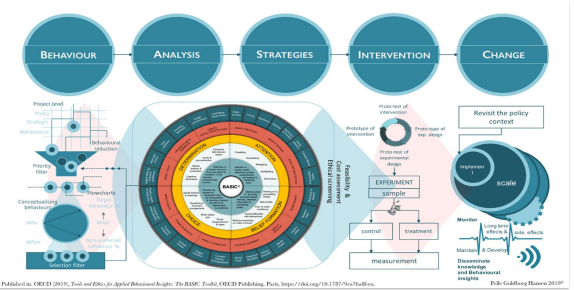

Staged approach to using the behavioural change wheel ₃

Therefore, at its simplest level we must understand:

- The BEHAVIOURS we were likely to encounter

- Take an approach that allowed us to ANALYSE as many aspects under consideration without

losing focus. - Develop clear and actionable STRATEGIES that would engage and have measurable impact.

- Develop a series of interconnected INTERVENTIONS that connected with the approach and

in a language that was salient to the business - Create a CHANGE roadmap with recurring patterns to counter cognitive load effect

exacerbated by the pandemic.

This approach follows cited and respected academic research delivered in a real world context

effectively and with impact.

In this case study I have intentionally focused on the motivational training that was collaboratively

developed to deliver a tailored solution into the organisation. A common mistake I have found is

that some change managers believe in the “cookie cutter” approach of simply repeating what

worked the last time out. However, the reality is that each instance needs to designed and

developed from first principles and not a “templated” approach to deliver the right outcomes that

endure and sustain in an organisation.

Finally, I am happy to report that the digital implementation has delivered the business case benefits

to date and furthermore has an adoption rate of more than double the industry average. Reaffirming

my belief in the use of behavioural science in a tailored and structured way to truly understand the

“how” and “what” and “when” and “who” in a people centred approach.

Dave Fryer the programme lead from Rolls-Royce commented: The programme was able to deliver a

significant value to the business prior to the asset being delivered which is often not the case. This

was because the programme was not a “pure play” approach by utilising different technology (e.g.,

optical recognition and digitisation techniques) and applying a meticulous approach to opportunity

identification the payback period was reduced significantly. Finally, Prior to the programme my

understanding of behavioural science and how it can be applied to IT transformation programme

was somewhat esoteric. Having seen how powerful this is in action and the results it can have in

supporting the delivery of the programme business case it’s certainly something I will be using going

forwards in future projects.

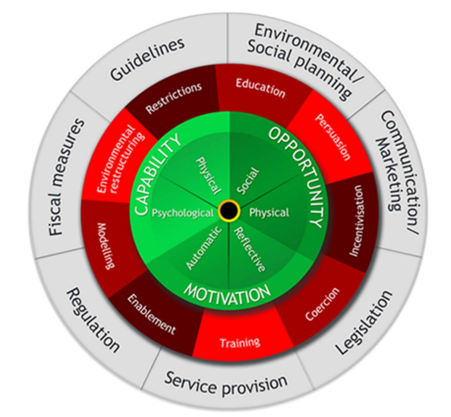

In triaging the behavioural issues, we reported the issues by anchoring our approach in a well

established behaviour change wheel ₄ (see below) signalling and differentiating between the

following;

- Capability: Users are not able to demonstrate a behaviour

- Opportunity: Users cannot demonstrate a behaviour due to lack of tools/conditions/technical difficulties, etc.

- Motivation: Users do not want to demonstrate a behaviour.

In summary addressing:

Capability + Opportunity + Motivation = Behaviour change

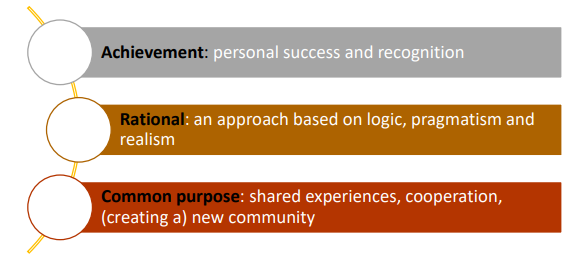

When concluding the design and approach we recognise that the Individual versus Enterprise

(Common purpose) approach was more powerful and by and large delivered the adoption through

the way we framed our communications, messages, language, guides and prompts. In behavioural

science terms we refer to this as cognitive framing ₂.

In commenting on this approach Iain Gladstone of Accenture stated: By putting behavioural science

at the core of the change management methodology as opposed to bolting it on as an “add on” this

resulted in it becoming embedded in each and every activity that was central to the adoption of the

technology and crucially the new ways of working. Through the scaling of experiments, randomised

control trials and being “led by the data” it gave us the flexibility to deliver an agile and truly iterative

transformation roadmap. Our biggest single lesson learnt were from the results achieved and insight

that a behavioural science led approach provided allowed us to elevate the conversation around

change and adoption to senior executives and sponsors on the programme. It created the “wow

factor” and provided us with a seat at the top table, in turn creating the sponsorship and stewardship

required to deliver a successful change programme.

In conclusion this led us to take an approach that I refer to as the Motivational ARC that is centred

on the individual and not at the Enterprise level. I have summarised this in the diagram below;

Some other key takeaways for us all are summarised as;

- In system and at point of use training (AppLearn: https://applearn.com/ )

- Curiosity had the greatest impact in driving engagement with training

- Externally recognised personal accredited certification gained through empirical learning/use.

- Short intervals between reward stages to motivate people to engage.

In summing up Franck L’Heureux commented: The Rolls-Royce team, led by David Loseby understood

the true value of digital transformation, which is to drive better ways of doing business, not simply

automating existing processes. By combining the right technology with effective behavioural

analysis, they were able to fundamentally improve their management of direct spend and suppliers.

This project should be viewed as a model for other procurement and supply chain leaders to emulate.

In writing this article I wish to cite the professionalism and dedication of some of the key players that

were instrumental in making the Rolls Royce digital implementation a great success:

Dave Fryer – Programme Lead (Rolls Royce)

Iain Gladstone – Change lead (Accenture)

Diletta Broggian– Communications Lead (Accenture)

Dr Diana Barea – Behavioural Science Advisor (Accenture)

Franck L’Heureux – Digital software Partner & CRO (Ivalua)

Jorge F. Guedes – System Implementation Programme Manager (Capgemini)

₁ According to Cognitive Load Theory (CLT), three types of cognitive load exist: intrinsic load,

extraneous or ineffective load, and germane or effective load. The intrinsic cognitive load refers to

cognitive load that is induced by the structure and complexity of the instructional material. Typically,

this can’t be influenced through training. The extraneous cognitive load refers to the cognitive load

caused by the format and manner in which information is presented. e.g., when training people and

asking then to consider multiple and disparate sources at once! Finally, the germane cognitive load

refers to cognitive load that is induced by learners’ efforts to process and comprehend the material.

The goal of CLT is to increase this type of cognitive load so that the learner can have more cognitive

resources available to solve problems.

₂ Essentially Cognitive framing or sometimes referred to as the Framing Effect is a cognitive bias that

explains how we react differently to things depending on how they are presented to us. Being aware

of and manipulating the way information is presented can highly influence how it is received.

Framing something in a certain way – through the use of image, words, context, etc. – will shape

assumptions and perceptions about it. Whether the positive gains or the negative losses are

highlighted will make a big difference.

₃ Michie S, Atkins L, and West R (2014). A guide to using the Behaviour Change Wheel. London:

Silverback Publishing.

₄ MICHIE S., ATKINS L., WEST R. The behaviour change wheel, A guide to designing interventions 1st

edition Great Britain: Silverback Publishing 2014: p 1003-1010.