Vladimir Gusev is an immigrant founder and technology entrepreneur with more than 15 years of experience building and scaling digital platforms across marketing, workforce marketplaces, and applied AI. His career spans the co-founding and exit of a top-ranked performance marketing agency, senior leadership roles in high-growth platform businesses, and hands-on work scaling complex, transaction-heavy systems across international markets.

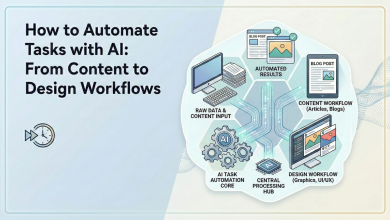

In this interview with AI Journal, Gusev reflects on how these experiences shaped his approach to building technology for highly regulated environments and why immigration, with its layered statutes, interpretive complexity, and high personal stakes, is one of the most challenging domains for applied AI. Drawing on lessons from scaling marketplaces and operational systems, he discusses the limits of automation, the importance of systematizing interpretation rather than replacing expert judgment, and what immigration reveals about where AI can create durable value across other rule-driven industries.

To begin, how did you get started in building technology platforms, and how did your background as an immigrant founder shape your decision to apply AI to immigration systems?

I co-founded CubeLine, a digital marketing agency, in 2009. Over about ten years, we grew it into a Top 10 agency by Tagline, Russia’s main digital industry ranking. We were certified partners of Yandex and Google, serving enterprise clients across the Global and Russian markets. My co-founder and I eventually sold the business through an M&A transaction. That whole experience taught me something I keep coming back to: if your growth depends on individual heroics, it won’t last. You need systems.

In 2020, I moved into marketplaces as VP of Growth at GigAnt, a workforce-as-a-service platform that became number one in its category in Eastern Europe. We raised over $6 million through Napers, scaled the business 10x over about two years, and grew from 200 to over 2,500 completed gigs per day, with over 100,000 independent workers on the platform.

After relocating to Argentina and obtaining a couple of US visas, I found myself navigating immigration systems firsthand and saw the same kind of operational complexity I had been solving for years, with very little technology addressing it.

Immigration combines formal statutes, regulatory guidance, and large volumes of unstructured text. From a systems perspective, why does this make it one of the most complex environments for applied AI?

The thing that makes immigration so hard to systematize is that it sits at the intersection of federal regulation, agency-level interpretation, and deeply personal stakes. A single case can involve statutory requirements, agency guidance, and administrative precedent – multiple layers of authority that an immigration attorney has to synthesize for each situation. And the consequences of getting it wrong aren’t abstract – it’s someone’s ability to live and work in a country. The technology that exists tends to focus on document management and forms rather than the interpretive layer underneath.

In your work, what did you observe about the gap between clearly defined legal rules and the inconsistent ways those rules are executed across real-world immigration workflows?

The formal structure looks straightforward, statutes define categories, regulations set requirements, and policy guidance fills in detail. The inconsistency starts when those rules are applied in real-world settings. Every practitioner I’ve worked with brings genuine expertise to case strategy, but the supporting operations – intake structure, evidence traceability, handoffs, quality checks – vary enormously, even within the same firm. I recognized this immediately because I’d seen the same pattern at CubeLine and GigAnt: when quality depends entirely on who handles a case rather than what system supports them, you get inconsistent execution even when the underlying expertise is strong. The gap isn’t in the legal knowledge, that was consistently impressive. It’s in the infrastructure surrounding it: how institutional knowledge gets preserved or lost, how lessons from one case inform the next.

You have emphasized that successful AI in regulated domains requires systematizing interpretation and decision logic, not just deploying models. What specific architectural or process principles proved essential in this context?

The most important thing was breaking cases down to their smallest meaningful units. At GigAnt, every quality issue could be traced to a specific point in the process – one worker, one shift, one client. Immigration is the same. Instead of treating a petition as one big document, you map each piece of evidence to the specific regulatory criterion it supports, with explicit logic for how that evidence relates to the criterion. The second principle was keeping legal interpretation separate from operational data. In our AI-native operating system, statutory text, regulatory guidance, and precedent decisions exist as distinct reference layers. That way, the AI can surface relevant patterns without mixing up what the law says, how it’s been interpreted, and what’s happened operationally.

How did building AI for immigration challenge common assumptions about automation, especially in environments dominated by legacy systems and human-driven processes?

The biggest assumption I had to unlearn was that automation means removing manual steps to increase speed. At CubeLine and GigAnt, that framing mostly worked. In immigration, it doesn’t work because you’re dealing with people’s legal status, their families, and their ability to stay in a country. Attorneys carry professional liability for every petition they file. So the model I arrived at is what I think of as role compression: AI handles the repetitive operational work, such as the intake normalization, completeness checks, evidence indexing, while attorneys keep the judgment work: case strategy, risk assessment, final sign-off. The goal is to remove friction. The legacy systems piece was equally humbling. Most practices run on general-purpose tools that aren’t built for this level of complexity. I assumed we could layer technology on top, the way we had at GigAnt. Instead, you have to build the structured foundation first, document parsing, entity extraction, case records that preserve context, and everything has to be auditable and overridable. Practitioners need to trust the system before they use it.

What original insights did your work in immigration reveal about where AI creates durable operational leverage in rule-driven industries, beyond short-term efficiency gains?

Once cases move through a standardized workflow, you start seeing patterns you couldn’t see before, where evidence tends to be missing, where rework happens most, and which completeness checks prevent last-minute problems. The key is what I’d call interpretation standardization: ensuring the system processes regulatory criteria consistently so you can meaningfully compare what’s working across different cases. As the system processes more cases, those patterns get sharper. Ultimately, you’re building a clearer picture of where preparation makes the biggest difference.

Based on these lessons, how can other highly regulated sectors, such as finance, healthcare, or government services, apply AI responsibly while maintaining compliance and consistency?

Any regulated service industry where expert judgment meets high-volume operations has this same dynamic. Healthcare compliance, financial advisory, and insurance underwriting all involve practitioners making complex interpretive decisions, while operational work that technology could handle better surrounds them. The principle that transferred most directly from GigAnt and CubeLine is what I think of as progressive autonomy: the system starts by handling simple tasks, proves reliability, and gradually takes on more responsibility as it earns trust. In immigration, that means the AI might start with document checklists and over time move to initial evidence assessment – but always with the attorney in control. The question then becomes how to scale this across an industry composed of thousands of small firms. The model we chose, which I wrote about recently, is named an AI-enabled roll-up. It works differently from selling software to the firms. You integrate directly into how the work gets done, owning the operational layer while the immigration lawyers own the legal decisions. That’s how AI stops being a tool and becomes infrastructure.

Looking forward, what do you believe distinguishes AI systems that demonstrate genuine expertise and long-term impact from those that fail to produce lasting organizational value?

Two things matter most. First, whether the AI actually captures in-house knowledge or just processes transactions. The risk with any AI tool is that it speeds things up without actually making the organization smarter. The systems that last are the ones that learn from how experts work and make that knowledge available to the whole team. Second, whether you’ve built what I’d call a full-stack AI company – one that powers the entire service workflow end-to-end, from intake through filing – or just bolted AI on top of existing tools. In immigration, that means the system needs to account for how evidentiary standards work, how regulatory interpretation layers onto statute, and why an experienced attorney might weigh one piece of evidence differently than another. You can’t get there by adding AI to someone else’s workflow. You have to build the infrastructure from inside the domain. That’s what the last fifteen years taught me – across MarTech, Workforce platforms, and now Immigration. The technology only works when it’s built on a genuine understanding of the work.