When you begin to learn Chinese online or work with an online Chinese teacher, you may first be a little shocked that Mandarin has tones! But did you know that around 55% of the world’s languages are tonal? It is nothing we cannot master! Mandarin Chinese uses four tones plus a neutral tone, which determine the meaning of words. Understanding why Mandarin developed tones and what happens when they are mispronounced provides good insights, but note that it is not as strict or horrible as you think! Getting them wrong sometimes will usually NOT affect understanding what you are saying, as often falsesly assumed!

Now, the tonal system was not always part of Chinese. Old Chinese, spoken before approximately 500 CE, did not have tones. Tones developed during the transition to Middle Chinese, fundamentally altering the language’s sound system. When certain “letters” at the ends of words disappeared, the pitch patterns that remained became distinctive features that carried meaning. This phenomenon is also known as Tonogenesis, and, guess what, may even happen to our languages over time! (Linguists believe)

The reason tones became necessary relates directly to the structure of Chinese. There are significantly fewer sound variants in Chinese than in most other languages. With a limited inventory of basic sounds, Chinese needed another dimension to distinguish between words. Tone provided that dimension, allowing the same syllable sound to carry multiple meanings based on pitch contour alone. The four tones of Mandarin each have distinct characteristics. The first tone is high and level, maintaining a steady pitch throughout. The second tone rises from middle to high pitch. The third tone starts at a middle pitch, dips low, then rises again, though in practice it often simply stays low when not in isolation. The fourth tone starts high and drops sharply to a low pitch. Additionally, there is a neutral tone that is pronounced quickly and lightly without specific pitch contour.

The consequences of incorrect tone usage range from minor confusion to complete miscommunication. MOST of the cases: it will not affect what you are saying! The most frequently cited example involves the syllable “ma,” which can mean mother, hemp, horse, or scold depending on the tone used. But this is only in isolation! There always is context, and, did you know that in many Chinese dialects mum in fact is the third tone?! So, we cannot be too strict about this. Context usually prevents total confusion in natural speech.

Nevertheless, certain tone errors do cause genuine misunderstandings. The words for “buy” and “sell” differ only in tone, and confusing these in a commercial transaction creates real confusion about the transaction’s direction. The verbs meaning “to ask” and “to kiss” also differ only in tone, and using the wrong tone transforms a polite question into an unexpectedly intimate statement… The difficulty of learning tones varies by linguistic background. Speakers of tonal languages generally find Mandarin tones easier to acquire than speakers of non-tonal languages. For speakers of European languages, which generally do not use pitch to distinguish word meaning, the tonal system represents an entirely new dimension of pronunciation that requires explicit attention.

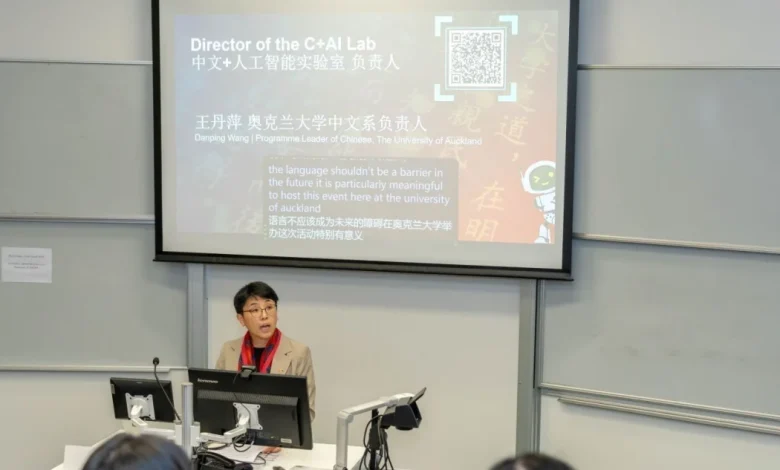

Institutions that teach Mandarin, such as GoEast Mandarin in Shanghai, typically emphasize tone training from the beginning of instruction. Early establishment of correct tone habits prevents the fossilization of errors that become difficult to correct later. Systematic exposure to tones across multiple speakers, combined with immediate feedback, proves effective for tone acquisition.

Native speakers acquire tones implicitly through exposure rather than through explicit instruction about pitch contours. Children learning Chinese do not consciously consider whether words use the third or fourth tone; the tonal patterns become encoded through repeated exposure to each word. This suggests that extensive listening to authentic speech is beneficial for learners, though adults generally require more explicit instruction than children do. The tonal nature of Mandarin does have compensating features. Once mastered, the system provides efficient disambiguation with minimal additional phonetic material. The musical quality that tones impart to the language is noted by many learners and speakers. The necessity of attending closely to pitch throughout speech training can enhance overall phonological awareness.