Business ecosystems aren’t a new concept.

Every industry that relies on partnerships, suppliers, or some form of a network of collaborators with a common interest in designing, developing, and distributing a product has to build a set of rules and mechanisms by which they can work together.

The problem is that many of these ecosystems have grown organically in a disconnected fashion and not by design.

A prime example is an automobile.

At our present rate of production and demand, the number of automobiles worldwide will exceed two billion by 2050 and by some projections as high as two-and-a-half billion.

The friction in that scenario is not in the factories—we could easily scale production to that level—but rather in the impact, it would have on urban congestion, energy use, safety, and pollution.

What makes the automobile an especially interesting player in illustrating the benefit of shifting to an ecosystem model is that it is a vital part of the much larger physical and digital ecosystem within which it operates, and yet, your automobile does not communicate with its local environment in any meaningful way.

If you stop to think about what single technology advance has most changed the experience of driving so far, it’s undoubtedly the integration of real-time GPS, which provides a way to intelligently connect to the larger ecosystem that the car is part of.

But why stop there?

Most of our world, but especially the structure of a city, is built around transportation.

The roadways, intersections, traffic lights, roundabouts (rotaries for our Boston readers), shopping and dining, are all part of an organically grown ecosystem that is loosely connected and coordinated.

However, each of these components of the city/transportation ecosystem generates friction that detracts from the experience of everyone involved.

So, what if we were to remove that friction?

It’s amazing how dramatically an industry, and more importantly an ecosystem, changes the moment friction is taken out of the equation.

Let’s go back to Uber for a minute.

Uber hasn’t just changed the way people move around in cities; it’s literally changing and transforming cities. Uber through its app gathers so many behavioral data points in real-time that it’s able to understand the large behaviors of a city.

Knowledge of our digital habits, needs for mobility, transactions, lifestyle, where and when we shop and eat, and the two billion rides people have taken using Uber, give it the ability to understand how our digital selves’ behaviors contribute to the efficiency of the entire ecosystem and all of its participants.

Today Uber provides this data to urban and city planners through a service called Movement, which anonymizes drivers’ patterns of behavior.

It’s a small step to get from there to a future where the same data is used as part of an integrated city-wide mesh that has the intelligence to not only personalize the transportation experience for an individual but to also minimize the overall impact of congestion, energy use, traffic flow, and safety.

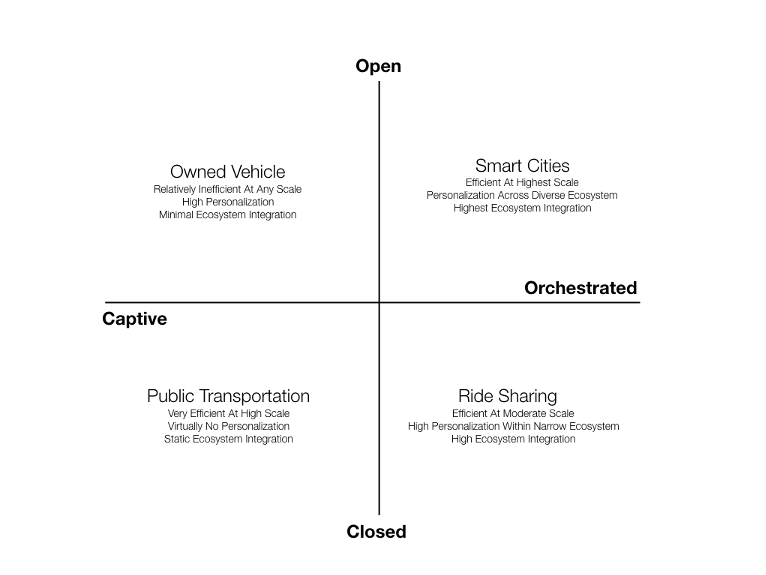

This approach is what we refer to as an open-orchestrated digital ecosystem in which the broadest possible range of intelligent devices, infrastructure, and digital-self all communicate with each other in order to enable the highest possible level of efficiency for the overall ecosystem and hyper-personalization for the individual.

Simply defined, a digital ecosystem is an orchestrated set of capabilities and constantly communicating devices across digitally connected businesses and consumers. The value of a digital ecosystem is four-fold:

- It reduces inherent friction across its network of partners;

- It creates a highly personalized experience for customers since it is able to leverage behavioral data collected across the ecosystem;

- Transparency across this same network of behavioral data enables it to predict and evolve with the markets it serves;

- Constant intelligent communication and awareness of each component in the ecosystem enable it to learn and evolve.

The third and fourth aspects of the digital ecosystem are arguably the most important and what differentiates it from ecosystems that grow organically and without the benefit of connected intelligence that can observe, learn, and decide. We know that may seem like a stretch, but later in this chapter, we will actually show you an example of how this is already being done today.

Ultimately, Digital ecosystems provide an alternative to the more traditional industrial era value chain on which to scale a business, but that only works if you can plug into that platform. Take Apple’s App Store. If you can work within the digital ecosystem of the App Store, then you have the potential to realize tremendous value, not just initially but through in-app purchases which are nearly frictionless for customers. While this isn’t an open-orchestrated but instead a closed-orchestrated ecosystem—because of Apple’s control over the apps it allows into its store—it is still a very effective digital ecosystem.

The digital ecosystem business model is to the behavioral business what telecommunications were to globalization. Both create a universal foundation on which you can build new value and competitive differentiation.

The difference is that digital ecosystems involve much more than just superficial communications; they require high transparency and trust since they cut deeply into nearly every aspect of how a business builds products, services, and customer experiences—to the point where the business has to reconfigure itself entirely around the customer experience, and more specifically, for our topic, to the personalized needs of each customer. This is why the notion of a digital-self, which bridges the physical and digital, is so critical in enabling communication between the many entities that make up the ecosystem.

Digital ecosystems are an essential part of any behavioral business model because the fundamental principle behind them is that individuals have personalized needs that a commoditized offering will always fall short of. In other words, observing and understanding customer behaviors is worthless to business and meaningless to the customer if the ecosystem cannot respond to those behaviors.

There’s also a significant benefit to ecosystems when it comes to mitigating risk. industrial era business models focus enormous energy on managing risk because there is no way to understand the degree of risk each in each transaction. The risk was not personalized—it was aggregated. The only option, in that case, is to spread risk across all transactions.

For example, let’s construct a hypothetical scenario around car insurance and risk. Today your insurance will vary based on your car’s value, where your car is garaged, the annual mileage, and your age and incidents in your driving history. You pay X each year and the insurance company calculates your risk at some factor of X that projects a profit based on the aggregated risk and premiums across everyone it insures. This means that even within any single category of risk, some drivers are still going to be a higher risk than others.

So, what if drivers could be insured each time they drive based on the risks of the route they take? And what if the car could also present the driver (or owner in the case of an AV) with a choice based on the road conditions, prior incidents, and the capabilities of the car? Route A is twenty minutes at five dollars, route B is two dollars and fifty cents at twenty-five minutes, and route C is twenty-five cents at forty-five minutes. By the way, it could be the case that a shorter route costs more than a longer route or that the same route costs different amounts for different drivers. The point is that the risk is now hyper-personalized to the situation at the moment. The insurance company still determines risk in order to meet the goal of its profit margins, but the owner has the choice to pay for the level of service they require. Nobody loses here since even a high-risk driver can now choose the lower risk routes. This can only be achieved at scale with the digital ecosystem model that we are describing in this chapter.

The fact is that risk is always best measured on an individualized basis, but an industrial era model built for scale doesn’t have the behavioral information or the capacity or the resources to do that.

Given the increasing complexity of all industries, we are convinced that one of the greatest contributors to economic growth for the remainder of the twenty-first century will be in rebuilding them with entirely new frictionless digital platforms that have the ability to use a hyper-personalized model.

However, there’s one wrinkle in the ecosystem fabric. If you noticed. we said “rebuild,” not “incrementally improve” or “re-engineer.”[KP1] That’s because every indication is that the economics and the speed of rebuilding far outweigh those of reengineering. The fundamental reason for this is not, as some would claim, a lack of vision or ambition to innovate. As we’ll see, its roots go back to the issues we began to introduce in Chapter 1 about the necessary shift from an industrial economy of scale business model to one that can respond to markets at the level of the individual consumer. In the same way that an old house with a cracked foundation, worn-out plumbing, and electrical systems, and wood rot from a leaking roof may take much longer and cost much more to renovate than to rebuild, many of the systems that today shore up these tired old industries are likely to suffer the same fate.

As industries undergo the transformation to digital ecosystems an entirely new set of opportunities begins to emerge. Not only because friction is reduced and the rate of innovation increases, but also because digital ecosystems provide the opportunity to capture behaviors throughout a product’s lifecycle and then build new services that are uniquely suited to each customer with relatively little effort. The result is that moving to a digital ecosystem redefines and significantly expands a company’s potential market space, while it also simplifies and reduces the effort expended to achieve a particular goal, whether it be getting you from point A to point B in the fastest or most pleasant (to you) way possible, or minimizing the carbon footprint of transportation within a city.

The ecosystem concept is by no means limited to just vehicles. For example take Nike, Lego, and Philips. Each took simple physical objects (shoes and apparel in case of Nike, bricks in case of Lego, and light bulbs in case of Philips) as the foundation for the creation of complex multi-layered platforms of very complex digital business ecosystems.

What’s especially important to understand in each of these cases is that the potential market for these companies was historically very compartmentalized. Their ecosystems were limited by their brand, the way in which customers experienced their products, and their partner and distribution channels.

The way traditional ecosystems operate limits the breadth and engagement of companies and brands. It would be like having an automobile that only operated in one of the fifty states in the USA. You could not cross a border into another state because every state had its own set of roadways and infrastructure, special fuel that only worked for cars in that state, mechanics that didn’t have a clue as to how any other state’s cars operated. It sounds ludicrous but it’s pretty close to the way companies have been limited in their ability to build across industry boundaries. It actually gets even worse because companies become so steeped in their own industry’s best practices that they often ignore the ways in which another industry might be addressing similar challenges in a novel way.

There’s nothing new in the idea of looking to other industries for best practices that can be applied in a novel way. One of our favorite examples is that of the Maclaren Baby Buggy (yes, a baby carriage) which was made by Owen Maclaren in 1965. Maclaren was an aviation engineer and a test pilot who had worked on one of World War II’s iconic fighters, the Spitfire. Maclaren had noticed his daughter dealing with the use of cumbersome baby carriages and so he created the first collapsible, portable, stowable baby buggy, which today is commonplace. The connection? The Spitfire was one of the first fighters to have retractable landing gear that folded neatly up into the plane’s wings.

Of course, these types of stories make for wonderful anecdotes but they are purely the result of serendipitous encounters and connections that seem to have no rhyme or reason. And you’d never rely on these sorts of chance encounters to build a business, right?

In a digital ecosystem, however, you can extend the reach with which these types of connections can be made with far greater ease, leveraging capabilities across nearly infinite spectrums of opportunity. The business you’re in doesn’t have to carry a label that confines it to a historical set of opportunities for innovation. This is especially true of organizations as they become more data-driven and start to use what we will call the five stages of digitalization in the next chapter.

If you’re Nike, you’re not in the shoe business; you’re in the sports, personal fitness, and health business. Nike took something basic, a pair of shoes which are hardly high-tech, and made them the core of a data-driven, experience-led ecosystem dominated by services that allow its customers to experience a better, healthier, more active and engaging life. Similarly, Lego isn’t supplying plastic bricks; it’s in the learning and entertainment business. Philips is not simply providing light bulbs; it’s in the business of creating a home experience.

Let’s look specifically at the case of Philips to describe the five distinct layers of value that can be created with a digital ecosystem. We’ll call these five layers the value-creation chain.[ii]

Layer 1 – The Physical Object:

The physical object, which in this case is the LED lightbulb, forms the first layer of the value-creation chain. It supplies the first direct, physical benefit to the user in the form of the function supplied by a light bulb. Because the light bulb is a physical object it, is always tethered to a location and can supply benefits at this layer only in its immediate environment—for example, an office, a kitchen, or a bedroom.

Layer 2 – The Sensor:

In layer 2, the physical object is equipped with computational skills provided by sensor technology and actuating elements. The sensors measure location data, while the actuating elements deliver services and thus generate insights and rewards for the user.

For example, a microwave sensor embedded in the LED light bulb continuously measures whether people are present in the space—reliably and at a low cost. The actuator turns the light on automatically when human presence is detected and off again when not, thereby supplying local benefits. Because the smart LED light bulb functions without a separate wired motion detector to discern presence the value of the bulb just increased dramatically without any additional effort on the part of the user. The bulb is now also able to capture behavior but in an invisible way since the user has added nothing new to the experience of screwing in a light bulb. However, the light bulb is still far from intelligent.

Layer 3 – Connectivity:

This is where the digital ecosystem starts to get interesting. The sensor technology and actuator elements in layer 2 are connected to the internet so that they become globally accessible. The light bulb can be addressed through an embedded radio module in order to transmit its status to authorized subscribers anywhere in the world at negligible marginal costs. In layer 3 we have the shift from something local and small to a global data-driven and context-relevant service that can connect with any other digital service or product.[KP2]

Layer 4 – Analytics:

Capturing data and connectivity per se do not deliver any added value by themselves. In layer 4, the data collected is stored, checked for plausibility, and classified. Then the findings of other web services are integrated with this data to arrive at consequences for the actuator elements—typically in a Cloud-based backend system. In layer 4 the on-and-off times in a household are collected, motion patterns are discerned, and the operating hours of individual light bulbs are recorded as well. Now the light bulb is not only an instrument for collecting data but also for exhibiting behaviors that apply this data to add value for the user.

Layer 5 – Digital Service/Behavioral:

At this, the final layer, the options provided by the previous layers are structured into digital services and packaged in a form suitable for entirely new product experience. Since the light bulb now “knows” some aspect of your behavior it can combine this knowledge with other smart devices, also at level 4 or 5, to make decisions. For example, if your bedroom light bulb went on at 3 a.m. and your kitchen light bulb went on at 3:03 a.m., followed by the refrigerator light going on at 3:04 a.m. [KP3] we could begin to make some determinations about what you might be doing. But when you couple this with the sensors and actuators in your bed, refrigerator, and microwave a much clearer picture starts to emerge.

Today we are somewhere between layers 2 and 4. Companies are attempting to use the data being collected to determine behavioral characteristics or patterns through algorithms and AI, but much of what’s being done involves teams of what are called Data Scientists pondering over the statistical patterns created by these massive collections of data. While this Big Data approach has merit, it is not a personalized approach to understanding the data. It is still using an old and very limited model of understanding behavior and delivering individualized value. That’s not to say that Big Data initiatives are fruitless. They are a quantum leap beyond focus groups and customer surveys, but they are just as far removed from the sort of individualized value creation that we are describing.

In our five-layer model, the physical objects, products, and devices are just the elementary particles used to form and build massive complicated data-rich ecosystems, which are constantly creating value by enhancing and adjusting products and services in real-time.

As you read this we’re sure that some of the earlier questions we raised about privacy are starting to resurface. Can we ever be comfortable with products and services that know us this well? Is the value worth it?

In an August 2017 article in the New York Times, Pamela Paul summed up the way many people feel about this degree of overwhelming change and disruption:

Disruption can be a positive force in the office, but at home, it feels the way disruption has always felt: intrusive and annoying. At home, at least, we have the power to pace the change, to choose the old over the new. These incremental lifestyle downgrades help calibrate a rate of technological change that might otherwise produce a resting state of whiplash. [iii]

While Paul’s comment is understandable it also feels to us like it’s throwing pebbles into a raging river hoping to stop the water from flowing. Disruption is destructive; there’s no way around it—it needs to be in order to dislodge the status quo.

The twentieth-century economist Joseph A. Schumpeter who coined the term Creative Destruction in his 1942 book Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy, said of disruptive competition, “[What counts is] competition from the new commodity, the new technology, the new source of supply, the new type of organization…competition which…strikes not at the margins of the profits and the outputs of the existing firms but at their foundations and their very lives.”

That’s exactly to sort of wholesale disruption we’re talking about in this chapter, digital disruption that threatens nearly every incumbent in every industry.

[i] “Uber Movement,” Uber Technologies website, accessed October 2, 2017, https://movement.uber.com/cities?lang=en-GB.

[ii] Georgios Achillias, “Phygital Platforms: Merging Physical And Digital,” Wipro Digital, accessed October 2, 2017, http://wiprodigital.com/2015/09/15/phygital-platforms-merging-physical-and-digital/.

[iii] Pamela Paul, “Save Your Sanity: Downgrade Your Life,” New York Times, August 18, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/18/opinion/sunday/technology-downgrade-sanity.html?smid=li-share.

[KP1]Add quotes around these for parallel structure? AUTH ADDED QUOTES

[KP2]Phrasing okay? Reads a little muddled AUTH ADDED THE WORD “AND” WHICH I BELIEVE CLARIFIES

[KP3]Chicago style usually calls for spelling out times that are full hours—like three in the morning—but because it looks odd to have one time spelled out and the rest as numerals, I’ve left it in this case. AUTH AGREED